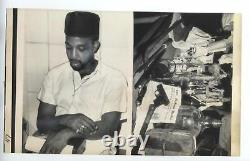

1964 Black Nationalist African American Muslim Press Photo Philadelphia Crime

1964 Black Nationalist photo measuring approximately 5 1/2 x 9 1/8 inches depicting. PHILADELPHIA: Black Nationalists leader Shayka Muhammad wearing a Fex, Goatee, and thin mustache (LP), is shown sitting in the 23rd Police District Headquarters, after 75, Philadelphia Police raided the headquarters of the "Black Nationalists". Police seized a large carton of "Molotov Cocktails", bricks, steel clubs, and a 22cal. Image can be seen here.

Philadelphia: Black Nationalism on Campus. Conversations with students at Penn and Temple show that black nationalism and assimilation are not the opposites they appear to be.From a white perspective, what looks like a sensible way to evaluate the thinking of black America is to imagine an axis with a cluster of views at each end. One cluster is politically liberal and culturally separatist; the other is conservative and assimilationist. Individual blacks' views can be plotted somewhere along the axis, with black-power and welfare-rights advocates falling near one cluster and conservatives who preach self-help near the other. Something like this model informs a great deal of the public discussion of black issues, so that the inner life of black America comes across in the white press as being dominated by an argument between positions roughly corresponding to white liberalism and white conservatism. But quite often bits of information emerge that indicate that the white categories aren't neatly applicable to black thought.

After President George Bush nominated Clarence Thomas for the Supreme Court, it emerged that in his college days this emblem of black conservatism had been a fan of Malcolm X. A few months later Vice President Dan Quayle came upon the Nation of Islam and commended it as an example of family values. In contrast to prominent Republicans' strange receptivity to black nationalism, Democrats seemed to go out of their way to condemn it. Back in the days when he was politically on the ropes, Bill Clinton helped revive his campaign by picking a fight with Sister Souljah, a nationalist lecturer and rapper. Practically the embodiment of the post-Second World War liberal tradition, wrote a book attacking black-nationalist excesses in the education system. Return to Flashback: African-American Education. Return to Flashback: Black History, American History.What's really going on in black America, then, doesn't fit the white categories. The main event intellectually for blacks seems to be ethnic and cultural identity, not the tensions between rich and poor, government and business, or labor and capital. To some extent it was ever thus. But black America traditionally was a thing unto itself, mostly poor and almost completely segregated. Its internal debates didn't matter to whites.

The never-ending argument over black identity continues on its own terms, not the outside world's -- only now it will probably have a growing effect on the outside world. Today black America is, as it always was, substantially poor, working-poor, and working-class, and substantially segregated, but its college-educated, white-collar middle class has grown significantly. This growth is the good news in American race relations. In the old days, before civil rights and before the mass migration to the North, it could be argued that better-off blacks had less contact with whites than poor blacks did: the poor often worked for whites as domestics and farm laborers, whereas the middle class often ran all-black institutions like churches, segregated schools, and funeral parlors.Now the reverse is true. Poor blacks are likely to be unemployed and to live in all-black ghettos, while many middle-class blacks work, study, and even live side by side with whites. The middle class's drama of ethnic assimilation has been accompanied by an unmistakable rise in cultural nationalism. This would seem paradoxical: if you're going to be living a whiter life, wouldn't the subject of blackness be less consuming? But members of every rising group feel intensely conscious of their ethnic identity at the moment that they enter the majority culture: they have to wrestle with social prejudice and with self-doubt.

That is why in the black middle class, which would appear to be fulfilling Martin Luther King Jr. S dream, not Malcolm X's, Malcolm X is now a much more important cultural icon than King. King's rhetoric of justice, delivered in a southern preacher's cadences, seems to have far less to do with the current situation than Malcolm's rhetoric of the psychological meaning of blackness. It seems almost inevitable that the first big heroic film biography by a black director would be about Malcolm X, not King.WANTING to look at the attitudes of upwardly mobile African-Americans on their own terms, rather than viewing them through the lens of national political debate, I recently spent some time talking to black students at two universities in Philadelphia: Temple and Penn. Temple University is a big, state-supported school that has always catered to ambitious people from modest backgrounds.

Its campus is encircled by trucks that serve every conceivable ethnic variation on the theme of the cheap, quick hot lunch, and that collectively underscore Temple's working-class aura. Temple has what might be the largest number of black students of any predominantly white university in America -- nearly 5,000 in a student body of 33,000 -- and it is in North Philadelphia, a black neighborhood.

The University of Pennsylvania is an Ivy League school, much smaller, much more prosperous, and populated mainly by the children of college-educated, upper-middle-class parents; among its black students last year were the sons of William Gray, the head of the United Negro College Fund, and Harold Ford, the congressman from Memphis. Out of a total of 11,000 undergraduates, Penn has only 700 who are black. Its campus is on the edge of West Philadelphia, which is generally thought of as a black ghetto. Whereas Temple has the feeling of being part of a black neighborhood, Penn has the feeling of being threatened by a black neighborhood. Temple's race-relations problems have a brawling, blue-collar cast -- for example, the school was briefly home to a white student union that was sympathetic to David Duke's National Association for the Advancement of White People -- whereas Penn's are played out more politely but may be more severe.Each school is home to one of the most famous black professors in the country, but the difference between them is emblematic: Penn's black superstar is Houston Baker Jr. An English professor who, in addition to being the founder and head of Penn's Center for the Study of Black Literature and Culture, is the current president of the leading mainstream organization in his field, the Modern Language Association. Temple's is Molefi Asante, the leader of the Afrocentrist movement, who is revered within his discipline and generally scorned outside it. The people I spoke with at the two schools were not really a representative sampling, because I picked people with nationalist inclinations; I wanted to parse nationalism, not conduct a survey on its popularity.

For these students, the power of nationalism is that it addresses all their major preoccupations, intellectual, psychological, and economic: it can be studied as an academic subject, it is a natural part of the adolescent identity crisis, and it provides a way of framing career decisions. I got the feeling, though, that in the long run nationalism, which appears to be a rejection of assimilationism, will bring most of them closer to the center of American life. THE outside world probably views black nationalism as an anti-white, separatist ideology that grew out of the black-power movement of the 1960s and posits a withdrawal by blacks from the language, culture, values, and economy of white America. Actually, prominent black-nationalist figures had emerged by the middle of the nineteenth century (the novel Blake, or The Hats of America, by Martin Delany, is a nationalist riposte to Uncle Tom's Cabin), and a nationalist strain can be discerned in the thinking of many or even most of the leading actors in African-American history.

Washington's views as "technocratic black nationalism, " and also devotes a chapter to arguing that Washington's archrival, W. DuBois, was a nationalist too: after all, DuBois was involved in Pan-African movements for most of his life, and died a citizen of Ghana. The peak of nationalism as a mass movement came more than three quarters of a century ago, during the heyday of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association. The reason nationalism is so confusing from the point of view of traditional white political divisions is that on the one hand, it attempts to promote black businesses and other forms of self-help, resists the notion that the federal government can help blacks, and is uninterested in liberal causes like civil rights and integration, but on the other hand, its world view would strike most whites as being left-wing. The nationalist tendency would be to mistrust white society and to celebrate political-liberation movements around the world, especially in Africa.Thus Elijah Muhammad, the founder of the Nation of Islam and a mentor to both Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan, was legendary among blacks as a proponent of traditional values, an opponent of drugs and alcohol, a nurturer of ghetto small businesses, and a savior of habitual criminals, prostitutes, and other hard-core members of the underclass -- but he was perceived by the larger world, not inaccurately, as a preacher of hatred. Mass-movement nationalism -- Garvey's, Elijah's, and Washington's, too -- was aimed at a constituency ranging from the very poor up to about the independent-artisan or small-farmer level; the black elite was more integrationist. But during the late 1960s and early 1970s college-educated blacks embraced nationalism, and mass-movement nationalism withered. The net result was that nationalism became more a matter of intellectual and cultural attitude and less a precise life blueprint.

Today there isn't much going on in the way of ghetto nationalist organizations striving to create entirely black economic institutions -- hence the famous lack of black-owned grocery stores. The home of nationalism is the campus, and for the first time in history many of the leading nationalists are tenured professors at majority-white universities rather than leaders of black organizations. This creates a difficulty: what are black students who embrace nationalism supposed to do after they graduate, since there isn't much of a black economy for them to join?NEARLY all the students I met stoutly insisted that they were going to find black careers. It seemed that the students at Temple were more likely than the ones at Penn actually to do this, because many Temple graduates find work in municipal bureaucracies -- school systems, welfare departments -- where the work force is substantially black, whereas Penn students are likely to be headed for the professions, which are overwhelmingly white. What was noteworthy was the impulse: remaining within black America was the right thing to do, and integration was the wrong.

The rough equivalent for white students, at least at eastern liberal-arts colleges, would be the choice between working for "social change" and pursuing a business career. You hear allegiance pledged to the former but find that the path actually followed in most cases is closer to the latter. Why is integration perceived as bad? First, because the students see black America as being in a crisis -- one that they, as its most fortunate children, are morally obliged to try to help solve. Second, because embracing integration looks perilously similar to rejecting blackness, one's own and the rest of the race's.Finally, because they perceive life in white America as being a constant, endless, draining struggle against prejudice. This last point touches on one of the great differences between blacks' and whites' views of American life. Many whites see being black, once you've made it out of the ghetto, as a big advantage: they think blacks are constantly getting little breaks that whites don't.

Many blacks have exactly the opposite view: race will always be an extra burden. The cost of housing is higher for blacks. The risk of crime is higher.

Nearly every social relationship with whites eventually arrives at a chilling moment of revelation of the hard inner kernel of racism. At work the assumption of inferiority is ever present; affirmative action underscores it, but is the only way even to get in the door.

A black college student's nationalism can be divided in half: part of it is a working out of one's relationship with black America, and part is the working out of one's relationship with white America. The students at Temple are more focused on the former, the students at Penn on the latter. A Temple student is far likelier than a Penn student to be personally in touch with the social and economic disaster in the ghettos, and therefore to be looking to nationalism to provide a vision of the meaning of blackness which is more uplifting than the daily reality of inner-city life. AFROCENTRISM, the creed of Temple's African-American Studies Department, has been attacked so often for being less an academic discipline than a self-esteem enhancement program that its leading figures now routinely insist that it isn't therapeutically motivated and aims only to document the enduring influences of ancient African civilizations. Still, it's hard to find any Afrocentrist material in which the urge to improve the image of blackness among blacks isn't detectable.

Molefi Asante has recently been distancing Afrocentrism from the extreme wing of academic black nationalism. For example, when I spoke with him, he completely dismissed the work of the "melanin theorists" -- the best-known is the infamous Leonard Jeffries Jr. Of the City University of New York, but a number of them are scattered around the country -- who, incredibly, study such matters as whether black infants are superior to white infants in motor skills. Some of the graduate students I met in the department were much more friendly to the melanin theory, however.

Asante also made a point of not criticizing whites as a group; instead, he sketched out a picture of a pluralistic society in which no group would be "hegemonic" and each would be "centered" in its own heritage: Whites shouldn't have to wear Mandinka clothes, and I shouldn't have to wear English suits. Afrocentrism's intellectual godfather is Cheikh Anta Diop, the author of The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality (1974), a Senegalese scholar who died in 1986. Culturally, the discipline has connections to what's left of the black-power movement. Bobby Seale, the former national chairman of the Black Panther Party, is on the staff of the African-American Studies Department at Temple, and Asante maintains close relations with Maulana Karenga, a professor at California State University at Long Beach, who in the 1960s developed a set of African-American spiritual concepts and rituals, among them Kwanzaa, a holiday celebrated the week after Christmas.

Asante views Temple's department, which is the only one in the country that grants a Ph. In African-American studies, as academically mainstream: he requires, for instance, that doctoral candidates be able to read the documents used in their research in the language in which they were written -- often Swahili. Many of the graduate students in African-American studies at Temple will wind up as academic Afrocentrists. Undergraduates who take courses in the department tend to want nationalism to provide them with something less well defined than a career but more important: an ordering principle by which to live. Everybody in an undergraduate group I met with was seeking a way to avoid both rejecting black culture and accepting the specific culture they had seen around them while they were growing up -- a culture that one of the students, Major Jackson, who had recently transferred to Temple, summarized in an autobiographical poem he wrote.

The strewn trash, the vacant. Lots, the empty houses, the old. The jamaican top-shelf weed at block. High on senseless gang-bang deaths. At the blumberg high-rise projects. Parasitic kisses of fly-girl Rashida. Sportin' 1/2-of-Africa's gold reserve. Adidas sweat suit, and the latest Nike's. Our conversation was filled with a mixture of embittered wonderment over conditions in post-civil-rights America, idealism, and sweeping oversimplifications. Here is part of it. MAJOR JACKSON: One evening when I was at Philadelphia College of Textiles, a drunk white boy from upstate Pennsylvania called me a nigger. He said it at a party as if I was supposed to laugh along with him. I rebelled with my fist. That's what led me to leave that school. CECIL GRAY: My great-great-grandfather was born in slavery.A white man raped an African woman; he was the result of that rape. The man made the mother put the child on a tree stump so the sun would turn him black.

He was fourteen or fifteen when slavery ended. AHMAD: I'm one of the only ones among my peers in high school who's alive and doesn't have a record. I'm not any different from them, but I came from an Islamic household. My parents were very strict. Outside the house, I was with the guys on the corner.

I'll give you one example. I was a young guy, sixteen years old, and I used to surround myself with older boys who weren't so spiritual. One day they took me to a dope house. A lady came in, about forty-five, an addict. I thought she must be somebody's mother. But she wanted heroin on credit. At one point a guy said,'Anybody want to do anything to this bitch? So she went around the room and did things. Everybody's filthy, everybody's talking. Then the guy calls her over and says,'Lay down.Everybody's laughing and slapping five. I'm sitting there and thinking,'Wadud, you're sixteen, why don't you feel anything?

GRAY: My sister was classified as a genius, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. By tenth grade she had read every book in the library. But for the last one and a half years in high school she was bored. Of course, at that time a black person couldn't attend a white school, which might have had materials that would have held her attention. She dropped out and got married. Now she's just on the planet. She just gets the stamps and the welfare. She sometimes gives herself away. There's a handful of white men who sit around a table.... They work out the art of oppression. That's what they do. And the average white person hears this and says,'I don't believe that. I'm not interested in conspiracy theories. AHMAD: I have an obligation: How can I not try to help black folk? I have to do it. I understand my position is limited, but I have to do something. I have to ask every day what I'm doing.... I plan on being a physician and starting my own clinic. JACKSON: I plan on teaching. I'd like to teach young African-American students. GRAY: I'm an African man. That's who I'm going to be.... For a number of years I have been talking about building a school. I'm going to do that. For Africans, who will be fluid-fluent in the so-called mainstream but also anchored in being African, and in our particular mission as African people. IT would be unusual to hear such sentiments, or to find an avowed Afrocentrist, at Penn, which has a reputation for preparing a much more select group for much loftier futures.The prevailing view about Penn among blacks is that it has tightened up its admissions and financial-aid standards over the years, and has thus become a more demanding, even hostile, place. "My class was the last one run on Great Society principles, " says Robert Arnold Wilson, a lawyer who graduated from Penn in 1975 and teaches political science part-time there. It was almost as if they drove a bus to every black urban neighborhood in America and said,'Anybody who has a chance to get out, come on!

We had almost two hundred blacks in the freshman class. We weren't Main Line blacks -- not the talented tenth.

He went on: The Bakke case met me when I came home. You could cut that tension with a knife. We had thirty-two blacks in my law-school class. We knew by the way white folks looked at us that we took one of their friends' places. They said,'These black folks don't deserve to be here. We said,'You owe us something. They said,'My grandfather came over from Russia; I don't owe you anything. Now Penn has slightly fewer black students, and they come from somewhat more affluent backgrounds: more private schools, more integrated neighborhoods. In 1985 a bitter racial controversy broke out. A white legal-studies lecturer at Wharton named Murray Dolfman asked some black students in his class to summarize the contents of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.When they couldn't, he told them they should know such things, because they were the descendants of slaves and the amendments were aimed at them. When word of the incident got around, it generated a fierce response among blacks who felt that it symbolized the disrespectful attitude toward them at Penn. Things have quieted down since then, but nobody considers Penn to be a race-relations paradise. Many black students at Penn see themselves as being in an essentially unfriendly white environment -- and they believe that the path to success will lead them into more such environments. Nationalism is a kind of emotional safe harbor.

"Many black students are coming to terms with who they are -- exploring their roots, " Elijah Anderson, a sociology professor at Penn, told me. A good number of students have grown up in predominantly white suburbs. One of the luxuries of being a college student is that you have the time to contemplate the meaning of your life. Some students dabble in nationalism and then go to Wharton and live in predominantly white neighborhoods.Farrakhan has come here a couple of times, and students were very curious. Some clapped, but most of these students are not moving into the inner-city ghetto when they leave school. I spent an evening with a small group of Penn students who live in DuBois House, which is the only dormitory in the Ivy League designated for students in African-American studies. Shortly after DuBois House was established, twenty years ago, in response to black students' demands, the NAACP threatened to sue on the grounds that it was separatist housing. The association withdrew its threat when it learned that the top two floors of the building were integrated graduate-student housing; DuBois House takes up the bottom two floors.

I asked the students -- most of whom said they had come to Penn because of its outstanding undergraduate business program -- what they planned to do after graduation. Here is some of what they said. MARTIN DIAS: I'd like to take what Penn has given me and use it in my own community. A lot of my friends want to open businesses, but I have to get over my risk aversion. ROBERT SMITH: You and the rest of the race!

DIAS: There are few black businesses on Fifty-second Street [a commercial thoroughfare of West Philadelphia]. I had a summer job at State Street Bank in Boston. They were really nice, but I don't want to work there. Being black is going to hinder me. We don't socialize together. I don't play golf. I don't like white parties with no rap music.So I won't be promoted. SMITH: That doesn't happen with Asians. They don't socialize, and they do well. I saw an Asian woman there who worked twelve years without a promotion.

SMITH: My career goal is to redevelop black America based on real-estate acquisition. You can get a job with a corporation, but where are you put? I'm not interested in being assistant vice-president for liaison human-resource personnel.... Look at the black community -- your grandmother's community.You move in, with your degree, you're upgrading the neighborhood. And you get kids who come out with some identity, and some friends.

Doesn't it make more sense than get ripped off, screwed up, and have your kids turn out wrong, in the name of integration? DIAS: I bet FIFTY of the black students at Penn will live in black neighborhoods.Ten percent will work for black companies. Then we got onto the subject of how it feels to be black at Penn.

TREASREA CORNELIUS: There's always an air about you. I have a couple of white friends. But we don't start on the same level. You're coming from different planets.

You can't tell somebody what it's like to be black. DIAS: I'm aware that if I say something in class, I represent black people. DIAS: I have to be extra articulate.

Then they say,'You're so articulate, Martin! There's a parenthesis at the end of every sentence:'for a black person.

FROM a distance it would be easy to worry that the black middle. Class wants to opt out of national life and create a psychologically separate black principality.

Afrocentrism, rap music, and other strains of contemporary nationalism provide plenty of evidence to support this view. But up close it's almost impossible to maintain. Outside the tiny world of academic black studies, the number of unintegrated black middle-class berths in American society is shrinking, not growing. It's as if an irresistible tidal force were pulling middle-class blacks toward white America. Nationalism and assimilation are therefore now linked, not opposing, forces. Very few nationalists ask their followers not to join the mainstream economy; I asked Molefi Asante if you could be an Afrocentrist and work for IBM and live in the suburbs, and he unhesitatingly said yes. And very few assimilationists see no need to shore up black identity. The chairman of the Afro-American Studies Department at Harvard and a critic of what he calls "black nationalist voodoo texts" (students jokingly call his tutorial for usually nationalism-besotted sophomores "Deprogramming 101"), nevertheless told me, What I want to see happen is black people with a strong social conscience learning to function through and in the center of American society. When you get to Wall Street and you bump into the glass ceiling, there's a kind of armament it provides. But if rejection of American society didn't seem to run very deep among the students I talked to, cynicism about it did. They knew that you get ahead by following a set of rules, but the rules seemed arbitrary to them. I didn't sense much feeling that the system -- the whole superstructure of tests and grades and admissions offices and evaluations and promotions and raises -- has been constructed in accordance with high moral principles. Maybe the day will come when the country seems to blacks to be as outstandingly fair as it does to many whites. Until then even blacks who have become financially successful will be much likelier than whites to regard the familiar American pattern of social, political, and economic results with a measure of skepticism. Black Nationalism and the Call for Black Power. Smallwood, Assistant Professor, Black Studies Department, University of Nebraska, Omaha. Much of African American history has embodied the struggle for overcoming negative social forces. Manifested in both a pre- and post- slave society. Throughout most of American history, laws and social. Mores and folkways have forced African Americans to seek various alternatives that would enable them to. Realize their potential by seeking opportunities for intellectual, economic, political self-determination and. Black scholars have generally identified two tendencies of African Americans seeking to. Realize their full potential in society: the desire for integration by emphasizing full participation as United. States citizens, and call for Nationalism where Blacks would be independent from society either. Physically, culturally or psychologically, emphasizing collective action of African Americans based on. Shared heritage and common concerns. In this paper I will examine Black Nationalism, and discuss key. African American advocates of this ideology as an expression for African Americans attempting to resolve. The desire for Black independence and self-determination goes back to the eighteenth century with the. Formation of the African Methodist Episcopal Church by Richard Allen. In the early nineteenth century. The proliferation of the question of slavery in a democratic society fueled pro and anti-slavery forces. Contributing to division in the United States and eventually leading to the Civil War.Nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Black people were faced with the very grim prospect of social. Economic and political oppression in society. It is at this point that the issue of Black Nationalism arises. Wilson Moses states that the concept of Black Nationalism in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Were based first on a "subject" people under political, social and cultural domination through outside. Military occupation, and their desire to break away from foreign rule. In other cases, it represented the. Desire to unite traditionally disunited people; it attempts to unify politically all of these peoples whether.They are residents of African territories or descendants of those Africans who were disposed by the slave. The roots of Black Nationalism in the 1800s can be found in the colonization movement which addressed. Black emigration from the United States to Africa and Latin America.

McCartney suggests that a Black's. Desire for emigration was to gain political freedom and independence not possible for Blacks as a minority. Group: [Martin] Delaney sums up the major theme in the [Black] Nationalist credo when he says that. Every people should be the originators of their own schemes, and creators of the events that lead to their.

Delaney continues that since African-Americans are a minority in the United States, where many. And almost insurmountable obstacles present themselves' a separate Black Nation is necessary in the march. To self-determination (McCartney, 1992: 16).Black supporters of Nationalist ideology disagreed with those supporting an integrationist approach, such. As the Abolitionist Movement and leaders such as Frederick Douglass. People were an important part of the United States and had a stake in securing their freedom and staying in. Black historians John Hope Franklin and Alfred Moss observe the contradictory position.

Of pro-slavery Southerners also supporting Black emigration. As a result, Black and White abolitionists. Were skeptical of these Southerners' interest in emigration as a viable solution to ending slavery. Surmises that Southerners took this position to circumvent the national influence of anti-slavery forces and.

Get rid of free Blacks in the South. (Franklin and Moss, 1992: 174).

Though the Black Nationalism represented in the discussion of emigration in the early nineteenth century. Was neither financially feasible nor widely popular among Black people, it did provide an ideological.

Perspective on Black political thought that would surface again in the twentieth century with the Marcus. Marcus Garvey and the UNIA.

Ann's Bay, Jamaica in 1887, Marcus Mosiah Garvey was raised in a majority Black society. Garvey was afforded opportunities for learning that were not available to the. His father was well-read and had established a library in his home. For whom he worked as apprentice printer, also kept a library and understood the power of the "word". He eventually arrives in the United States in 1916 and seeks to provide a program for. Millions of disenfranchised Blacks to address their economic, political and educational plight during the.Garvey was attracted to aspects of Booker T. Washington's program of economic. Independence through self-help, which he felt would be more practical for the masses of poor Black people. In 1918, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) as a better alternative for.

Black people than interracial organizations such as the NAACP and the National Urban League. Of the fierce resistance to Black integration among Whites in the U. Would be the best chance for Blacks to realize their full potential as human beings culturally socially.

Colin notes that Garvey's UNIA had a strong educational component... Would learn to believe in themselves, in their race, and it was through the UNIA-ACL sponsored programs.The UNIA-ACL Civil Service Board, The Universal Black Cross Nurses Corps, The African Legions of the. Corporation; activities: The International Conventions of the Negro Peoples of the World; The Women's. Industrial Exhibition; educational institutions: The School of African Philosophy, the Booker T. Washington University, and Liberty University; and instructional materials: The Universal Negro.

Catechism, The Negro World, and the Black Man, that African [Americans] would receive the type of. Education they needed, education of self (Colin, 1996: 54). Garvey clearly used education in the form of programs and newspapers to teach Black people about. Economic and social uplift through collective action.Garvey's socio-political philosophy of Black. Nationalism, expressed in the UNIA, emphasized cultural pride, social separation and economic.

When examining the importance of Garvey for African Americans, Scipio Colin states. No other race leader had inspired such hope in the hearts of the people since the orations of Frederick. Douglass, and incorporated these inspirations (their aspirations) into practical adult education programs. His emphasis on racial pride, political and economic self-determination, proved to be a powerful message. For African Americans during the early twentieth century.An important influence on Malcolm X's political. Malcolm pointed out in his autobiography that his parents were followers.

Of Marcus Garvey and members of the UNIA, thus impacting Malcolm and siblings at an early age. This early exposure to Black Nationalism was important in providing a. Foundation that would prepare Malcolm to later embrace Black Nationalism fully after his departure from. The Nation of Islam (Malcolm X, 1992: 3-7).

Malcolm X: Political Influences and Evolution. The influence of Black Nationalism can also be found in the ideological formation of the Nation of Islam in.

After becoming a member of the NOI in the late 1940s, Malcolm X. Adhered to the organization's adaptation of Garvey's socio-political philosophy of Black Nationalism. Emphasizing group empowerment through cultural pride, economic development and social separation. During the period of 1953 through early 1964, Malcolm was restricted to a position of non-engagement on. Civil Rights and other social issues affecting African Americans.

As leader of the NOI, Elijah Muhammad. Forbade all members from participation in Civil Rights organizations, marches or any political activity in. 149-157; Perry, 1990: 207-212; and Essien-Udom, 1962: 177-178. During the late 1950s the NOI moved.Away from the political rhetoric of Black Nationalism and focused more on religious teachings to address. It was during the period of the early 1960s that Malcolm, an advocate for improving. African American life, began to privately question the NOI's role in improving the conditions of African.

Malcolm X believed that the organization, with its resources, could do more to address the. Plight of all African Americans and not just. His views were probably influenced, by the action oriented organizations such as the. Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and student groups like the Student Non-violent.Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which became the foundation of the Civil Rights Movement of the late. In 1963 Malcolm began to change his public rhetoric, aligning himself more with. It was this change that would lead him to seek cooperation with the.

Politically active organizations of the Civil Rights Movement (Goldman, 1979, 115-116). Research on Malcolm X as a political figure examines his political ideology and use of his power as an. Organizational leader to develop a greater sphere of influence for the Nation of Islam in the African. As National Representative and minister of the New York Mosque, Malcolm was in. The position to hold a national forum to examine the African American condition in the United States. Thet extent to which he changed his political ideology in the last year of his life is the subject of debate and. Malcolm X's position on politics and the African American community, at the very least. Indicates his attempt to internationalize the struggle against racism, linking Black oppression in the U. Colonial oppression of Blacks on the African continent. This ultimately leads to Malcolm embarking on. Two trips to Africa in 1964 in an effort to solicit the support of African leaders. 363; Clarke, 1990: 215-216; Goldman, 1979: 206-208. Several authors make a closer examination of Malcolm X showing that he adopted a philosophy of Black. Nationalism, and, thus laid the groundwork for the Black Power and Cultural Nationalist Movements of the. Late 1960s Karenga, 1994: 175-176. To broaden the struggle against Black oppression, Malcolm X sought.When examining diverse views on Malcolm X's political life, a. Common theme discusses Malcolm X's activism to relieve poverty and suffering in African American.

In the course of his political life, Malcolm X worked within local Black communities. Organizing residents to join the NOI as an answer to their social struggles. With his rise in the organization. He then used the media as a national voice for Black suffering in society. After his departure from the NOI.Malcolm X attempted to internationalize the struggle for African Americans and include a more diverse. Group of people in the struggle for Black self-determination.

Black Nationalism as an alternative to integration goes back over one hundred years, as Black leaders. Explored alternative political and social ideology to address racial discrimination against African.Americans in the United States. In the Twentieth Century, Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X became the two. Dominant figures emphasizing traditional Black Nationalism and influencing a generation of individuals. And organizations to implement their ideology. The Nation of Islam, led by Elijah Muhammad and.

Malcolm X, The Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee, led by Stokely Carmichael's call for Black. Power in the late 1960s, The Black Panther Party, led by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Grassroots organizations used Nationalist philosophy advocated by Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X, to. Address problems of poverty inadequate housing and police brutality, to take ownership of their. Communities through collective social action.

Malcolm X:The Man and His Times. An Original Man: The Life and Times of Elijah Muhammad.

"Marcus Garvey: Africentric Adult Education for Self-Ethnic Reliance" in. Freedom Road: Adult Education of African Americans Peterson, E. Black Nationalism: A search for Identity. (1994) From Slavery to Freedom.The Death and Life of Malcolm X. (1994) Introduction to Black Studies. Los Angeles: University of Sankore Press. The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Black Power Ideologies: An Essay in African American. Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Photographic Images\Photographs". The seller is "memorabilia111" and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay.

- Antique: No

- Type: Photograph