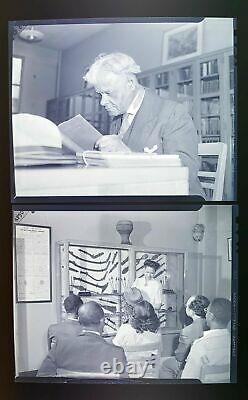

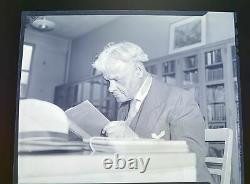

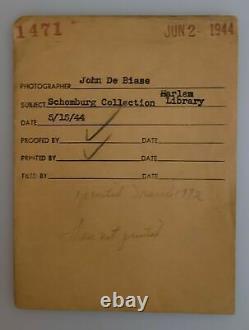

Harlem African American Negatives Vintage Manhattan Schomberg 1944 Black Culture

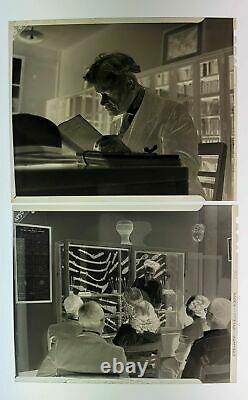

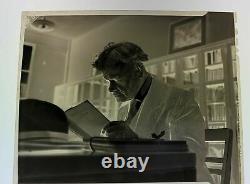

TWO 4X5 INCH NEGATIVES FROM 1944 OF SCHOMBERG COLLECTION HARLEM LIBRARY TAKEN BY PHOTOGRAPHER JOHN DE BIASE. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is a research library of the New York Public Library and an archive repository for information on people of African descent worldwide. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is a research library of the New York Public Library (NYPL) and an archive repository for information on people of African descent worldwide.

Located at 515 Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) between West 135th and 136th Streets in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, it has, almost from its inception, been an integral part of the Harlem community. It is named for Afro-Puerto Rican scholar Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. The resources of the Center are broken up into five divisions, the Art and Artifacts Division, the Jean Blackwell Hutson General Research and Reference Division, the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, the Moving Image and Recorded Sound Division, and the Photographs and Prints Division. In addition to research services, the center hosts readings, discussions, art exhibitions, and theatrical events. It is open to the general public.

[1] Later in 1901 Carnegie formally signed a contract with the City of New York to transfer his donation to the city to then allow it to justify purchasing the land to house the libraries. [2] McKim, Mead & White were chosen as the architects and Charles Follen McKim designed the three-story library building at 103 West 135th Street in the Italian Renaissance Palazzo mode. [3] At its opening on July 14, 1905, the library had 10,000 books[4] and the librarian in charge was Gertrude Cohen. World War II-era WPA poster promoting use of the Schomburg Collection of the New York Public Library (Federal Art Project 1941-43). In 1920, Ernestine Rose, a white woman born in Bridgehampton in 1880, became the branch librarian.

[6] She quickly integrated the all-white library staff. [7] Catherine Allen Latimer, the first African-American librarian hired by the NYPL, was sent to work with Rose as was Roberta Bosely months later.

[8] Some time later Sadie Peterson Delaney became employed at the branch. [9] Together, they created a plan to assist integrating reading into the lives of the library attendees and cooperated with schools and social organizations in the community. In 1921, the library hosted the first exhibition of African-American art in Harlem; it became an annual event. [11] The library became a focal point to the burgeoning Harlem Renaissance. [7] In 1923, the 135th Street branch was the only branch in New York City employing Negroes as librarians, [12] and consequently when Regina M. Anderson was hired by the NYPL, she was sent to work at the 135th Street branch. Rose issued a report to the American Library Association, in 1923, which stated that requests for books about Negroes or written by Negroes had been increasing, [14] and that the demand for professionally trained colored librarians was also. [15] In late 1924, Rose called a meeting, with attendees including Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, James Weldon Johnson, Hubert Harrison, that decided to focus on preserving rare books, and solicit donations to enhance its African-American collection. [16] On May 8, 1925, it began operating as the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints, a division of the NYPL. In 1926, the center's collection won acclaim with the addition of Schomburg's personal collection. By donating his collection, Schomburg sought to show that black people had a history and a culture and thus were not inferior to other races. [20] About 5,000 objects in Schomburg's collection were donated.In 1929, Anderson was desirous of a promotion and enlisted the help of W. Du Bois and Walter Francis White when she was being discriminated against by not being promoted. After letters of intervention on her behalf by Du Bois and White, and a boycott of the library by White, Anderson was promoted and transferred to the Rivington Street branch of the NYPL. By 1930, the Center had 18,000 volumes.

[4] In 1932, Schomburg became the first curator of his collection, until his death in 1938. [23] In 1935, the Center developed a project to deliver books once a week to those handicapped severely enough that they could not make it to the library. Reddick became the second curator of the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature. [25] At the behest of Reddick, in October 1940, the entire Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints was renamed the Schomburg Collection of Negro History and Literature. In 1942 Rose retired[27] after an extension was built onto the rear of the building, at a time when the library had 40,000 books.

Dorothy Robinson Homer replaced her as Branch Librarian, after the Citizen's Committee of the 135th Street Branch Library specifically requested a Negro to replace Rose. After the extension was built, the library became known as the Countee Cullen Library branch, [29] and the 135th Street Library is still considered the original location of the Countee Cullen branch, [30] although that name is now only used for the extension itself on West 136th Street. Homer created a room of books just for young adults and created the American Negro Theatre in the basement that spawned the play Anna Lucasta, which was moved to Broadway. She kept the emphasis on building a community center for art, music and drama. She put on art exhibits that favored unknown, young artists of all races.

After the outbreak of WWII, Homer started a program of monthly concert recitals in the auditorium to enhance public spirit, but the demand by performers and audience members to continue the practice made it permanent. In 1948, Jean Blackwell, later Jean Blackwell Hutson, was named the director of the Center. [34] In a 1966 speech, Hutson warned of the perilous status of the Schomburg collection. In 1971, the Center began being supported by the privately funded Schomburg Corporation. [36] The next year, funds by New York City were allocated to renovate the building at 103 West 135th, [37] and it was renamed the building of the Schomburg Collection for Research in Black Culture.

[38] Simultaneously, the entire Schomburg collection was rounded up from various branch libraries and transferred to the Center. [39] In 1972, it was designated as one of NYPL's research libraries. In 1973, a building on the west side of Lenox ave between 135th and 136th was bought so that it could be demolished and a new building could be constructed. The location was chosen due to its proximity to other community agencies and because it was the scene of the Harlem Renaissance. [40] In 1978, the building on 135th Street between Lenox and 7th Avenues was entered into the National Register of Historic Places.

[41] In 1979, it was formally listed in the NRHP. The entrance to the Center. In 1980, a new Schomburg Center was founded at 515 Lenox Avenue. [36] In 1981, the original building on West 135th Street which held the Schomburg Collection was designated a New York City Landmark. [43] In 2016, both the original and current buildings, now joined by a connector, were designated a National Historic Landmark. Wray became the director of the Center. [45] Protests began over Wray's decision to not hire an African-American man to head the Center's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Books Division and instead hired Robert Morris. [46] In 1983, Wray resigned to pursue academic research[45] and Catherine Hooker was named acting director. Howard Dodson became the director in 1984, at a time when the Schomburg was primarily a cultural center visited by tourists and schoolchildren and its research facilities were known only to scholars. [20] In 1984, the Schomburg's collection was at 5 million.In 1984 attendance was 40,000 a year. [48] As early as 1984, the Schomburg was recognized as the most important institution in the world for collections of art and literature of people in Africa or its diaspora. [49] In 1983, a scholars-in-residence program started at the center. [50] In 1986, an exhibit entitled Give me your poor...

In 1991, completion of additions to the Schomburg Center were completed. The new center on Malcolm X was expanded to include an auditorium and a connection to the old landmark building on 135th. [53] The Art and Artifacts Division and the Moving Image and Recorded Sound Division were moved into the old landmark building. [54] In 2000, the Schomburg Center held an exhibition titled "Lest We Forget: The Triumph Over Slavery", which later went on tour around the world for more than a decade under the sponsorship of UNESCO's Slave Route Project.

In 2005, the center held an exhibition of letters, photographs and other material related to Malcolm X. The Schomburg Center had 120,000 visitors a year; by 2010, Dodson announced he would retire in early 2011. In 2007, the Schomburg Center was one of the sponsors of the African Burial Ground National Monument. Video icon Tour of the Schomburg Center conducted by Khalil Gibran Muhammad, May 27, 2015, C-SPAN. Following Howard Dodson's announcement of his retirement in 2010, [20] Khalil Gibran Muhammad, great-grandson of Elijah Muhammad and professor of history at Indiana University, was announced as Dodson's replacement. [48] In the summer of 2011, Muhammad became the fifth director of the Schomburg. His stated goals were for the Schomburg to be a focal point for young adults and to collaborate with the local community, to not only reinforce its pride, but also for the Center to be a gateway for revealing the history of Black people worldwide. [56] In July, the Center began an exhibit of Malcolm X footage and prints entitled Malcolm X: the Search for Truth. Bob Gore photographs Kevin Young and Claudia Rankin.On August 1, 2016, the New York Public Library announced that poet and academic Kevin Young would begin as director of the Schomburg in the late fall of 2016. [57][58] During Young's four-year tenure, attendance increased by 40%, to 300,000 visitors per year. Young stepped down at the end of 2020 in order to assume a new position as director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture logo.

The Schomburg Collection was considered, in 1998, as consisting of the rarest, and most useful, Afrocentric artifacts of any public library in the United States. [62] At least as late of 2006, it is viewed as the most prestigious for African-American materials in the country. [63] As of 2010, the Collection stood at 10 million objects, [20] The Center contains a signed, first edition of a book of poems by Phillis Wheatley, archival material of Melville J. Herskovits, [64] John Henrik Clarke, [65] Lorraine Hansberry, [66] Malcolm X and Nat King Cole. [20] The collection includes the files, or papers of the International Labor Defense, the Civil Rights Congress, the Symphony of the New World, [67] and the National Negro Congress.

Price, [69] Ralph Bunche, Léon Damas, William Pickens, [70] Hiram Rhodes Revels, Clarence Cameron White. The files of the South African Dennis Brutus Defense Committee (restricted). [71] The collection also includes manuscripts of Alexander Crummell[72] and John Edward Bruce, manuscripts of Slavery, Abolitionism and on the West Indies, and letters and unpublished manuscripts of Langston Hughes.It includes some papers from Christian Fleetwood, Paul Robeson (restricted), [73] Booker T. Washington, [74] and Schomburg himself.

It includes musical recordings, black and jazz periodicals, rare books and pamphlets, and tens of thousands of art objects. [75] The Center's collection includes documents signed by Toussaint Louverture and a rare recording of a speech by Marcus Garvey. The Center also acts as the literary representative of the heirs of Claude McKay. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City.

It is bounded roughly by Frederick Douglass Boulevard, St. Nicholas Avenue, and Morningside Park on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Harlem area encompasses several other neighborhoods and extends west to the Hudson River, north to 155th Street, east to the East River, and south to Martin Luther King Jr.Boulevard, Central Park, and East 96th Street. Originally a Dutch village, formally organized in 1658, [4] it is named after the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands. Harlem's history has been defined by a series of economic boom-and-bust cycles, with significant population shifts accompanying each cycle. [5] Harlem was predominantly occupied by Jewish and Italian Americans in the 19th century, but African-American residents began to arrive in large numbers during the Great Migration in the 20th century.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Central and West Harlem were the center of the Harlem Renaissance, a major African-American cultural movement. With job losses during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the deindustrialization of New York City after World War II, rates of crime and poverty increased significantly.

[6] In the 21st century, crime rates decreased significantly, and Harlem started to gentrify. The area is served by the New York City Subway and local bus routes. It contains several public elementary, middle, and high schools, and is close to several colleges including Columbia University and the City College of New York. Central Harlem is part of Manhattan Community District 10.

[1] It is patrolled by the 28th and 32nd Precincts of the New York City Police Department. The greater Harlem area also includes Manhattan Community Districts 9 and 11 and several police precincts, while fire services are provided by four New York City Fire Department companies. Post offices and ZIP Codes. A map of Upper Manhattan, with Greater Harlem highlighted. Harlem proper is the neighborhood in the center. Harlem is located in Upper Manhattan, often referred to as "Uptown" by locals.The three neighborhoods comprising the greater Harlem area-West, Central, and East Harlem-stretch from the Harlem River and East River to the east, to the Hudson River to the west; and between 155th Street in the north, where it meets Washington Heights, and an uneven boundary along the south that runs along 96th Street east of Fifth Avenue, 110th Street between Fifth Avenue to Morningside Park, and 125th Street west of Morningside Park to the Hudson River. [7][8][9] Encyclopædia Britannica references these boundaries, [10] though the Encyclopedia of New York City takes a much more conservative view of Harlem's boundaries, regarding only central Harlem as part of Harlem proper.

Central Harlem is the name of Harlem proper; it falls under Manhattan Community District 10. [7] This section is bounded by Fifth Avenue on the east; Central Park on the south; Morningside Park, St. Nicholas Avenue and Edgecombe Avenue on the west; and the Harlem River on the north. [7] A chain of three large linear parks-Morningside Park, St.

Nicholas Park and Jackie Robinson Park-situated on steeply rising banks, form most of the district's western boundary. Fifth Avenue, as well as Marcus Garvey Park (also known as Mount Morris Park), separate this area from East Harlem to the east. [7] Central Harlem includes the Mount Morris Park Historic District.

West Harlem (Manhattanville and Hamilton Heights) comprises Manhattan Community District 9 and does not form part of Harlem proper. The two neighborhoods' area is bounded by Cathedral Parkway/110th Street on the south; 155th Street on the north; Manhattan/Morningside Ave/St. Nicholas/Bradhurst/Edgecombe Avenues on the east; and Riverside Park/the Hudson River on the west. Manhattanville begins at roughly 123rd Street and extends northward to 135th Street. The northernmost section of West Harlem is Hamilton Heights.

East Harlem, also called Spanish Harlem or El Barrio, is located within Manhattan Community District 11, which is bounded by East 96th Street on the south, East 138th Street on the north, Fifth Avenue on the west, and the Harlem River on the east. It is not part of Harlem proper. Further information: Morningside Heights, Manhattan § SoHa controversy.

In the 2010s some real estate professionals started rebranding south Harlem and Morningside Heights as "SoHa" (a name standing for "South Harlem" in the style of SoHo or NoHo) in an attempt to accelerate gentrification of the neighborhoods. "SoHa", applied to the area between West 110th and 125th Streets, has become a controversial name.

[12][13][14] Residents and other critics seeking to prevent this renaming of the area have labelled the SoHa brand as "insulting and another sign of gentrification run amok"[15] and have said that "the rebranding not only places their neighborhood's rich history under erasure but also appears to be intent on attracting new tenants, including students from nearby Columbia University". Multiple New York City politicians have initiated legislative efforts to curtail this practice of neighborhood rebranding, which when successfully introduced in other New York City neighborhoods, have led to increases in rents and real estate values, as well as "shifting demographics". Representative Hakeem Jeffries attempted but failed to implement legislation that would punish real estate agents for inventing false neighborhoods and redrawing neighborhood boundaries without city approval.[16] By 2017, New York State Senator Brian Benjamin also worked to render illegal the practice of rebranding historically recognized neighborhoods. Politically, central Harlem is in New York's 13th congressional district. [17][18] It is in the New York State Senate's 30th district, [19][20] the New York State Assembly's 68th and 70th districts, [21][22] and the New York City Council's 7th, 8th, and 9th districts. Harlem, from the old fort in the Central Park, New York Public Library. Main article: History of Harlem.

Before the arrival of European settlers, the area that would become Harlem (originally Haarlem) was inhabited by a Native American band, the Wecquaesgeek, dubbed Manhattans or Manhattoe by Dutch settlers, who along with other Native Americans, most likely Lenape, [24] occupied the area on a semi-nomadic basis. As many as several hundred farmed the Harlem flatlands. [25] Between 1637 and 1639, a few settlements were established. [26][27] The settlement of Harlem was formally incorporated in 1660[28] under the leadership of Peter Stuyvesant. During the American Revolution, the British burned Harlem to the ground.

[30] It took a long time to rebuild, as Harlem grew more slowly than the rest of Manhattan during the late 18th century. [31] After the American Civil War, Harlem experienced an economic boom starting in 1868. The neighborhood continued to serve as a refuge for New Yorkers, but increasingly those coming north were poor and Jewish or Italian.

[32] The New York and Harlem Railroad, [33] as well as the Interborough Rapid Transit and elevated railway lines, [34] helped Harlem's economic growth, as they connected Harlem to lower and midtown Manhattan. Apartment building in Central Harlem. A condemned building in Harlem after the 1970s.The Jewish and Italian demographic decreased, while the black and Puerto Rican population increased in this time. [35] The early-20th century Great Migration of black people to northern industrial cities was fueled by their desire to leave behind the Jim Crow South, seek better jobs and education for their children, and escape a culture of lynching violence; during World War I, expanding industries recruited black laborers to fill new jobs, thinly staffed after the draft began to take young men.

[36] In 1910, Central Harlem population was about 10% black people. By 1930, it had reached 70%.Starting around the time of the end of World War I, Harlem became associated with the New Negro movement, and then the artistic outpouring known as the Harlem Renaissance, which extended to poetry, novels, theater, and the visual arts. So many black people came that it threaten[ed] the very existence of some of the leading industries of Georgia, Florida, Tennessee and Alabama.

[38] Many settled in Harlem. By 1920, central Harlem was 32.43% black. The 1930 census revealed that 70.18% of central Harlem's residents were black and lived as far south as Central Park, at 110th Street. However, by the 1930s, the neighborhood was hit hard by job losses in the Great Depression. In the early 1930s, 25% of Harlemites were out of work, and employment prospects for Harlemites stayed bad for decades. Employment among black New Yorkers fell as some traditionally black businesses, including domestic service and some types of manual labor, were taken over by other ethnic groups. Major industries left New York City altogether, especially after 1950. Several riots happened in this period, including in 1935 and 1943. There were major changes following World War II. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Harlem was the scene of a series of rent strikes by neighborhood tenants, led by local activist Jesse Gray, together with the Congress of Racial Equality, Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU), and other groups.These groups wanted the city to force landlords to improve the quality of housing by bringing them up to code, to take action against rats and roaches, to provide heat during the winter, and to keep prices in line with existing rent control regulations. The largest public works projects in Harlem in these years were public housing, with the largest concentration built in East Harlem. [41] Typically, existing structures were torn down and replaced with city-designed and managed properties that would, in theory, present a safer and more pleasant environment than those available from private landlords. Ultimately, community objections halted the construction of new projects. From the mid-20th century, the low quality of education in Harlem has been a source of distress.

In the 1960s, about 75% of Harlem students tested under grade levels in reading skills, and 80% tested under grade level in math. [43] In 1964, residents of Harlem staged two school boycotts to call attention to the problem. In central Harlem, 92% of students stayed home. [44] In the post-World War II era, Harlem ceased to be home to a majority of the city's black people, [45] but it remained the cultural and political capital of black New York, and possibly black America.

By the 1970s, many of those Harlemites who were able to escape from poverty left the neighborhood in search of better schools and homes, and safer streets. Those who remained were the poorest and least skilled, with the fewest opportunities for success.

[48] The city began auctioning its enormous portfolio of Harlem properties to the public in 1985. This was intended to improve the community by placing property in the hands of people who would live in them and maintain them.

After the 1990s, Harlem began to grow again. Between 1990 and 2006 the neighborhood's population grew by 16.9%, with the percentage of black people decreasing from 87.6% to 69.3%, [39] then dropping to 54.4% by 2010, [50] and the percentage of whites increasing from 1.5% to 6.6% by 2006, [39] and to "almost 10%" by 2010. [50] A renovation of 125th Street and new properties along the thoroughfare[51][52] also helped to revitalize Harlem. Welcome to Harlem sign above the now defunct Victoria 5 cinema theater on 125th st. In the 1920s and 1930s, Central and West Harlem was the focus of the "Harlem Renaissance", an outpouring of artistic work without precedent in the American Black community. Though Harlem musicians and writers are particularly well remembered, the community has also hosted numerous actors and theater companies, including the New Heritage Repertory Theater, [29] National Black Theater, Lafayette Players, Harlem Suitcase Theater, The Negro Playwrights, American Negro Theater, and the Rose McClendon Players. The Apollo Theater on 125th Street in November 2006.The Apollo Theater opened on 125th Street on January 26, 1934, in a former burlesque house. The Savoy Ballroom, on Lenox Avenue, was a renowned venue for swing dancing, and was immortalized in a popular song of the era, "Stompin' At The Savoy". In the 1920s and 1930s, between Lenox and Seventh Avenues in central Harlem, over 125 entertainment venues were in operation, including speakeasies, cellars, lounges, cafes, taverns, supper clubs, rib joints, theaters, dance halls, and bars and grills.

133rd Street, known as "Swing Street", became known for its cabarets, speakeasies and jazz scene during the Prohibition era, and was dubbed "Jungle Alley" because of "inter-racial mingling" on the street. [56][57] Some jazz venues, including the Cotton Club, where Duke Ellington played, and Connie's Inn, were restricted to whites only.

Others were integrated, including the Renaissance Ballroom and the Savoy Ballroom. In 1936, Orson Welles produced his black Macbeth at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem.[58] Grand theaters from the late 19th and early 20th centuries were torn down or converted to churches. Harlem lacked any permanent performance space until the creation of the Gatehouse Theater in an old Croton aqueduct building on 135th Street in 2006. Spiritual African Drummer on 135th Street between Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard and Frederick Douglass Boulevard. From 1965 until 2007, the community was home to the Harlem Boys Choir, a touring choir and education program for young boys, most of whom are black. [60] The Girls Choir of Harlem was founded in 1989, and closed with the Boys Choir.

Harlem is also home to the largest African American Day Parade, which celebrates the culture of African diaspora in America. The parade was started up in the spring of 1969 with Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

As the Grand Marshal of the first celebration. Arthur Mitchell, a former dancer with the New York City Ballet, established Dance Theatre of Harlem as a school and company of classical ballet and theater training in the late 1960s. The company has toured nationally and internationally. Generations of theater artists have gotten a start at the school. By the 2010s, new dining hotspots were opening in Harlem around Frederick Douglass Boulevard.

[63] At the same time, some residents fought back against the powerful waves of gentrification the neighborhood is experiencing. In 2013, residents staged a sidewalk sit-in to protest a five-days-a-week farmers market that would shut down Macombs Place at 150th Street. Black Ivory in Harlem 2017.

Many R&B/Soul groups and artists formed in Harlem. The Main Ingredient, Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers, Black Ivory, Cameo, Keith Sweat, Freddie Jackson, Alyson Williams, Johnny Kemp, Teddy Riley and others got their start in Harlem.

Manhattan's contributions to hip-hop stems largely from artists with Harlem roots such as Doug E. Fresh, Big L, Kurtis Blow, The Diplomats, Mase or Immortal Technique. Harlem is also the birthplace of popular hip-hop dances such as the Harlem shake, toe wop, and Chicken Noodle Soup.

In the 1920s, African American pianists who lived in Harlem invented their own style of jazz piano, called stride, which was heavily influenced by ragtime. This style played a very important role in early jazz piano[65][66]. Religious life has historically had a strong presence in Black Harlem. The area is home to over 400 churches, [67] some of which are official city or national landmarks. [68][69] Major Christian denominations include Baptists, Pentecostals, Methodists (generally African Methodist Episcopal Zionist, or "AMEZ" and African Methodist Episcopalian, or "AME"), Episcopalians, and Roman Catholic. The Abyssinian Baptist Church has long been influential because of its large congregation. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints built a chapel on 128th Street in 2005. Many of the area's churches are "storefront churches", which operate in an empty store, or a basement, or a converted brownstone townhouse. These congregations may have fewer than 30-50 members each, but there are hundreds of them. [70] Others are old, large, and designated landmarks.Especially in the years before World War II, Harlem produced popular Christian charismatic "cult" leaders, including George Wilson Becton and Father Divine. Mosques in Harlem include the Masjid Malcolm Shabazz formerly Mosque No.

7 Nation of Islam, and the location of the 1972 Harlem mosque incident, the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood and Masjid Aqsa. Judaism, too, maintains a presence in Harlem through the Old Broadway Synagogue. A non-mainstream synagogue of Black Hebrews, known as Commandment Keepers, was based in a synagogue at 1 West 123rd Street until 2008. St Martin's Episcopal Church, at Lenox Avenue and 122nd Street.

Hotel Theresa building at the corner of Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building, at the same intersection as the Hotel Theresa. Many places in Harlem are official city landmarks labeled by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission or are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. 12 West 129th Street, a New York City landmark[72]. 17 East 128th Street, a New York City landmark[73].

369th Regiment Armory, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[74][69]. Abyssinian Baptist Church, a New York City landmark[75]. Apollo Theater, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[76][69]. Astor Row, a set of New York City landmark houses[68]:? 1, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, part of Central Park, a New York City scenic landmark and NRHP-listed site[77][69]. Central Harlem West-130-132nd Streets Historic District, a New York City landmark[78]. Dunbar Apartments, a New York City landmark[79]. Graham Court Apartments, a New York City landmark[80]. Hamilton Grange, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[81]. Harlem River Houses, a New York City landmark[82].Harlem YMCA, a New York City landmark[83]. Hotel Theresa, a New York City landmark[84]. Jackie Robinson YMCA Youth Center, a New York City landmark[85]. Langston Hughes House, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[86][69]. Macombs Dam Bridge and 155th Street Viaduct, a New York City landmark[87].

Manhattan Avenue-West 120th-123rd Streets Historic District, a NRHP historic district[69]. Metropolitan Baptist Church, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[88][69].

Minton's Playhouse, a NRHP-listed site[69]. Morningside Park, a New York City scenic landmark[89].

Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, a New York City landmark[90]. Mount Morris Park Historic District, a New York City landmark district[91].Mount Olive Fire Baptized Holiness Church, a New York City landmark[92]. New York Public Library 115th Street Branch, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[93][69]. Regent Theatre, a New York City landmark[94]. Schomburg Collection for Research in Black Culture, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[95][69].

Aloysius Roman Catholic Church, a New York City landmark[96]. Andrew's Church, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[97][69]. Philip's Protestant Episcopal Church, a New York City landmark[98].

Martin's Episcopal Church (formerly Trinity Church), a New York City landmark[99]. Nicholas Historic District, a New York City landmark district[100]. Paul's German Evangelical Lutheran Church, a New York City landmark[101]. Wadleigh High School for Girls, a New York City landmark[102]. Washington Apartments, a New York City landmark[103].

Other prominent points of interest include. Bushman Steps, stairway that led baseball fans from the subway to The Polo Grounds ticket booth. Harbor Conservatory for the Performing Arts.The Harlem School of the Arts. Harlem Fire Watchtower, a New York City landmark and NRHP-listed site[105][69]. New York College of Podiatric Medicine. Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine.

The demographics of Harlem's communities have changed throughout its history. In 1910, 10% of Harlem's population was black but by 1930, they had become a 70% majority. [6] The period between 1910 and 1930 marked a huge point in the great migration of African Americans from the South to New York. It also marked an influx from downtown Manhattan neighborhoods where blacks were feeling less welcome, to the Harlem area.[6] The black population in Harlem peaked in 1950, with a 98% share of the population (population 233,000). As of 2000, central Harlem's black population comprised 77% of the total population of that area; however, the black population is declining as many African Americans move out and more immigrants move in.

Harlem suffers from unemployment rates generally more than twice the citywide average, as well as high poverty rates. [107] and the numbers for men have been consistently worse than the numbers for women.

Private and governmental initiatives to ameliorate unemployment and poverty have not been successful. During the Great Depression, unemployment in Harlem went past 20% and people were being evicted from their homes. [108] At the same time, the federal government developed and instituted the redlining policy. This policy rated neighborhoods, such as Central Harlem, as unappealing based on the race, ethnicity, and national origins of the residents. [3] Central Harlem was deemed'hazardous' and residents living in Central Harlem were refused home loans or other investments.[3] Comparably, wealthy and white residents in New York City neighborhoods were approved more often for housing loans and investment applications. [3] Overall, they were given preferential treatment by city and state institutions. In the 1960s, uneducated blacks could find jobs more easily than educated ones could, confounding efforts to improve the lives of people who lived in the neighborhood through education. [3] Land owners took advantage of the neighborhood and offered apartments to the lower-class families for cheaper rent but in lower-class conditions.

[109] By 1999 there were 179,000 housing units available in Harlem. [110] Housing activists in Harlem state that, even after residents were given vouchers for the Section 8 housing that was being placed, many were not able to live there and had to find homes elsewhere or become homeless. [110] These policies are examples of societal racism, also known as structural racism. As public health leaders have named structural racism as a key social determinant of health disparities between racial and ethnic minorities, [111] these 20th century policies have contributed to the current population health disparities between Central Harlem and other New York City neighborhoods.

For census purposes, the New York City government classifies Central Harlem into two neighborhood tabulation areas: Central Harlem North and Central Harlem South, divided by 126th street. [112] Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Central Harlem was 118,665, a change of 9,574 (8.1%) from the 109,091 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 926.05 acres (374.76 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 128.1 inhabitants per acre (82,000/sq mi; 31,700/km2).

[113] The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 9.5% (11,322) White, 63% (74,735) African American, 0.3% (367) Native American, 2.4% (2,839) Asian, 0% (46) Pacific Islander, 0.3% (372) from other races, and 2.2% (2,651) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 22.2% (26,333) of the population.

Harlem's Black population was more concentrated in Central Harlem North, and its White population more concentrated in Central Harlem South, while the Hispanic / Latino population was evenly split. The most significant shifts in the racial composition of Central Harlem between 2000 and 2010 were the White population's increase by 402% (9,067), the Hispanic / Latino population's increase by 43% (7,982), and the Black population's decrease by 11% (9,544). While the growth of the Hispanic / Latino was predominantly in Central Harlem North, the decrease in the Black population was slightly greater in Central Harlem South, and the drastic increase in the White population was split evenly across the two census tabulation areas. Meanwhile, the Asian population grew by 211% (1,927) but remained a small minority, and the small population of all other races increased by 4% (142).The entirety of Community District 10, which comprises Central Harlem, had 116,345 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 76.2 years. This is lower than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.

Most inhabitants are children and middle-aged adults: 21% are between the ages of 0-17, while 35% are between 25 and 44, and 24% between 45 and 64. The ratio of college-aged and elderly residents was lower, at 10% and 11% respectively. [2] In 2018, an estimated 21% of Community District 10 residents lived in poverty, compared to 14% in all of Manhattan and 20% in all of New York City.

Around 12% of residents were unemployed, compared to 7% in Manhattan and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 48% in Community District 10, compared to the boroughwide and citywide rates of 45% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018, Community District 10 is considered to be gentrifying: according to the Community Health Profile, the district was low-income in 1990 and has seen above-median rent growth up to 2010.

In 2010, the population of West Harlem was 110,193. [117] West Harlem, consisting of Manhattanville and Hamilton Heights, is predominately Hispanic / Latino, while African Americans make up about a quarter of the West Harlem population. In 2010, the population of East Harlem was 120,000. [118] East Harlem originally formed as a predominantly Italian American neighborhood. [119] The area began its transition from Italian Harlem to Spanish Harlem when Puerto Rican migration began after World War II, [120] though in recent decades, many Dominican, Mexican and Salvadorean immigrants have also settled in East Harlem.[121] East Harlem is now predominantly Hispanic / Latino, with a significant African-American presence. NYPD Police Service Area 6, which serves NYCHA developments in greater Harlem. Central Harlem is patrolled by two precincts of the New York City Police Department (NYPD).

The 28th Precinct has a lower crime rate than it did in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 76.0% between 1990 and 2019. The precinct reported 5 murders, 11 rapes, 163 robberies, 235 felony assaults, 90 burglaries, 348 grand larcenies, and 28 grand larcenies auto in 2019. [125] Of the five major violent felonies (murder, rape, felony assault, robbery, and burglary), the 28th Precinct had a rate of 1,125 crimes per 100,000 residents in 2019, compared to the boroughwide average of 632 crimes per 100,000 and the citywide average of 572 crimes per 100,000.

The crime rate in the 32nd Precinct has also decreased since the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 75.7% between 1990 and 2019. The precinct reported 10 murders, 25 rapes, 219 robberies, 375 felony assaults, 110 burglaries, 315 grand larcenies, and 34 grand larcenies auto in 2019.

[129] Of the five major violent felonies (murder, rape, felony assault, robbery, and burglary), the 32nd Precinct had a rate of 1,042 crimes per 100,000 residents in 2019, compared to the boroughwide average of 632 crimes per 100,000 and the citywide average of 572 crimes per 100,000. As of 2018, Community District 10 has a non-fatal assault hospitalization rate of 116 per 100,000 people, compared to the boroughwide rate of 49 per 100,000 and the citywide rate of 59 per 100,000. Its incarceration rate is 1,347 per 100,000 people, the second-highest in the city, compared to the boroughwide rate of 407 per 100,000 and the citywide rate of 425 per 100,000. In 2019, the highest concentration of both felony assaults in Central Harlem was around the intersection of 125th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard, where there were 25 felony assaults and 18 robberies. The Harlem River Drive by the Ralph J.

Rangel Houses was also a hotspot, with 23 felony assaults and 10 robberies. Main article: Crime in Harlem.The Harlem riot of 1964. In the early 20th century, Harlem was a stronghold of the Sicilian Mafia, other Italian organized crime groups, and later the Italian-American Mafia. As the ethnic composition of the neighborhood changed, black criminals began to organize themselves similarly.

However, rather than compete with the established mobs, gangs concentrated on the "policy racket", also called the numbers game, or bolita in East Harlem. This was a gambling scheme similar to a lottery that could be played, illegally, from countless locations around Harlem. According to Francis Ianni, By 1925 there were thirty black policy banks in Harlem, several of them large enough to collect bets in an area of twenty city blocks and across three or four avenues.

[131] These bosses became financial powerhouses, providing capital for loans for those who could not qualify for them from traditional financial institutions, and investing in legitimate businesses and real estate. One of the powerful early numbers bosses was a woman, Madame Stephanie St. Clair, who fought gun battles with mobster Dutch Schultz over control of the lucrative trade.

[133] The practice continues on a smaller scale among those who prefer the numbers tradition or who prefer to trust their local numbers bank to the state. Statistics from 1940 show about 100 murders per year in Harlem, "but rape is very rare".

[134] By 1950, many whites had left Harlem and by 1960, much of the black middle class had departed. At the same time, control of organized crime shifted from Italian syndicates to local black, Puerto Rican, and Cuban groups that were somewhat less formally organized. [130] At the time of the 1964 riots, the drug addiction rate in Harlem was ten times higher than the New York City average, and twelve times higher than the United States as a whole.

Of the 30,000 drug addicts then estimated to live in New York City, 15,000 to 20,000 lived in Harlem. Property crime was pervasive, and the murder rate was six times higher than New York's average. Half of the children in Harlem grew up with one parent, or none, and lack of supervision contributed to juvenile delinquency; between 1953 and 1962, the crime rate among young people increased throughout New York City, but was consistently 50% higher in Harlem than in New York City as a whole. Injecting heroin grew in popularity in Harlem through the 1950s and 1960s, though the use of this drug then leveled off. In the 1980s, use of crack cocaine became widespread, which produced collateral crime as addicts stole to finance their purchasing of additional drugs, and as dealers fought for the right to sell in particular regions, or over deals gone bad.

With the end of the "crack wars" in the mid-1990s, and with the initiation of aggressive policing under mayors David Dinkins and his successor Rudy Giuliani, crime in Harlem plummeted. Compared to in 1981, when 6,500 robberies were reported in Harlem, reports of robberies dropped to 4,800 in 1990; to 1,700 in 2000; and to 1,100 in 2010. [137] Within the 28th and 32nd precincts, there have been similar changes in all categories of crimes tracked by the NYPD. There are many gangs in Harlem, often based in housing projects; when one gang member is killed by another gang, revenge violence erupts which can last for years. [138] In addition, the East Harlem Purple Gang of the 1970s, which operated in East Harlem and surroundings, was an Italian American group of hitmen and heroin dealers.

Harlem and its gangsters have a strong link to hip hop, rap and R&B culture in the United States, and many successful rappers in the music industry came from gangs in Harlem. [140] Gangster rap, which has its origins in the late 1980s, often has lyrics that are "misogynistic or that glamorize violence", glamorizing guns, drugs and easy women in Harlem and New York City. The Quarters of FDNY Engine Company 59/Ladder Company 30.

Central Harlem is served by four New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[142]. Engine Company 37/Ladder Company 40 - 415 West 125th Street[143]. Engine Company 58/Ladder Company 26 - 1367 5th Avenue[144].

Engine Company 59/Ladder Company 30 - 111 West 133rd Street[145]. Engine Company 69/Ladder Company 28/Battalion 16 - 248 West 143rd Street[146].Five additional firehouses are located in West and East Harlem. West Harlem contains Engine Company 47 and Engine Company 80/Ladder Company 23, while East Harlem contains Engine Company 35/Ladder Company 14/Battalion 12, Engine Company 53/Ladder Company 43, and Engine Company 91.

As of 2018, preterm births and births to teenage mothers are more common in Central Harlem than in other places citywide. In Central Harlem, there were 103 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 23 births to teenage mothers per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide), though the teenage birth rate is based on a small sample size. Central Harlem has a low population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 8%, less than the citywide rate of 12%.

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Central Harlem is 0.0079 milligrams per cubic metre (7.9×10-9 oz/cu ft), slightly more than the city average. Ten percent of Central Harlem residents are smokers, which is less than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers. In Central Harlem, 34% of residents are obese, 12% are diabetic, and 35% have high blood pressure, the highest rates in the city-compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively. In addition, 21% of children are obese, compared to the citywide average of 20%. Eighty-four percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is less than the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 79% of residents described their health as "good, " "very good, " or "excellent, " more than the city's average of 78%. For every supermarket in Central Harlem, there are 11 bodegas. The nearest major hospital is NYC Health + Hospitals/Harlem in north-central Harlem. The population health of Central Harlem is closely linked to influential social factors on health, also known as social determinants of health, and the impact of structural racism on the neighborhood. The impact of discriminatory policies such as redlining have contributed to residents' bearing worse health outcomes in comparison to the average New York city resident. This applies to life expectancy, poverty rates, environmental neighborhood health, housing quality, and childhood and adult asthma rates. Additionally, the health of Central Harlem residents are linked to their experience of racism. [149][150] Public health and scientific research studies have found evidence that experiencing racism creates and exacerbates chronic stress that can contribute to major causes of death, particularly for African-American and Hispanic populations in the United States, like cardiovascular diseases.Certain health disparities between Central Harlem and the rest of New York City can be attributed to'avoidable causes' such as substandard housing quality, poverty, and law enforcement violence - all of which are issues identified by the American Public Health Association as key social determinants of health. These deaths that can be attributed to avoidable causes are known as "avertable deaths" of "excess mortality'"in public health.

Access to affordable housing and employment opportunities with fair wages and benefits are closely associated with good health. [155] Public health leaders have shown that inadequate housing qualities is linked to poor health. [156] As Central Harlem also bears the effects of racial segregation, public health researchers claim that racial segregation is also linked to substandard housing and exposure to pollutants and toxins. These associations have been documented to increase individual risk of chronic diseases and adverse birth outcomes. [111] Historical income segregation via redlining also positions residents to be more exposed to risks that contribute to adverse mental health status, inadequate access to healthy foods, asthma triggers, and lead exposure.

Drew Hamilton Houses, a large low-income NYCHA housing project in Central Harlem. Asthma is more common in children and adults in Central Harlem, compared to other New York City neighborhoods. [157] The factors that can increase risk of childhood and adult asthma are associated with substandard housing conditions. [158] Substandard housing conditions are water leaks, cracks and holes, inadequate heating, presence of mice or rats, peeling paint and can include the presence of mold, moisture, dust mites. [159] In 2014, Central Harlem tracked worse in regards to home maintenance conditions, compared to the average rates Manhattan and New York City.Twenty percent of homes had cracks or holes; 21% had leaks and 19% had three or more maintenance deficiencies. Adequate housing is defined as housing that is free from heating breakdowns, cracks, holes, peeling paint and other defects.

Housing conditions in Central Harlem reveal that only 37% of its renter-occupied homes were adequately maintained by landlords in 2014. Meanwhile, 25% of Central Harlem households and 27% of adults reported seeing cockroaches (a potential trigger for asthma), a rate higher than the city average. Neighborhood conditions are also indicators of population: in 2014, Central Harlem had 32 per 100,000 people hospitalized due to pedestrian injuries, higher than Manhattan's and the city's average.

Additionally, poverty levels can indicate one's risk of vulnerability to asthma. In 2016, Central Harlem saw 565 children aged 5-17 years old per 10,000 residents visiting emergency departments for Asthma emergencies, over twice both Manhattan's and the citywide rates. The rate of childhood asthma hospitalization in 2016 was more than twice that of Manhattan and New York City, with 62 hospitalizations per 10,000 residents.

[157] Rates of adult hospitalization due to asthma in Central Harlem trends higher in comparison to other neighborhoods. In 2016, 270 adults per 10,000 residents visited the emergency department due to asthma, close to three times the average rates of both Manhattan and New York City.

Health outcomes for men have generally been worse than those of women. Infant mortality was 124 per thousand in 1928, meaning that 12.4% of infants would die. [160] By 1940, infant mortality in Harlem was 5%, and the death rate from disease generally was twice that of the rest of New York. Tuberculosis was the main killer, and four times as prevalent among Harlem citizens than among the rest of New York's population.

A 1990 study of life expectancy of teenagers in Harlem reported that 15-year-old girls in Harlem had a 65% chance of surviving to the age of 65, about the same as women in Pakistan. Fifteen-year-old men in Harlem, on the other hand, had a 37% chance of surviving to 65, about the same as men in Angola; for men, the survival rate beyond the age of 40 was lower in Harlem than Bangladesh. [161] Infectious diseases and diseases of the circulatory system were to blame, with a variety of contributing factors, including consumption of the deep-fried foods traditional to the South, which may contribute to heart disease.Harlem is located within five primary ZIP Codes. From south to north they are 10026 (from 110th to 120th Streets), 10027 (from 120th to 133rd Streets), 10037 (east of Lenox Avenue and north of 130th Street), 10030 (west of Lenox Avenue from 133rd to 145th Streets) and 10039 (from 145th to 155th Streets). Harlem also includes parts of ZIP Codes 10031, 10032, and 10035.

[162] The United States Postal Service operates five post offices in Harlem. Morningside Station - 232 West 116th Street[163]. Manhattanville Station and Morningside Annex - 365 West 125th Street[164].

College Station - 217 West 140th Street[165]. Colonial Park Station - 99 Macombs Place[166]. Lincoln Station - 2266 5th Avenue[167].

Investigate Harlem, an area of New York City that became a vibrant African American community in the early 1900s. Find out why people moved to Harlem and how its social and cultural environment nurtured writers and artists. Note what you learn in the chart. Central Harlem's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is higher than the rest of New York City. In Central Harlem, 25% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, more than the citywide average of 20%.

Additionally, 64% of high school students in Central Harlem graduate on time, less than the citywide average of 75%. The New York City Department of Education operates the following public elementary schools in Central Harlem:[168]. PS 76 A Phillip Randolph (grades PK-8)[169]. PS 92 Mary Mcleod Bethune (grades PK-5)[170]. PS 123 Mahalia Jackson (grades PK-8)[171].

PS 149 Sojourner Truth (grades PK-8)[172]. PS 154 Harriet Tubman (grades PK-5)[173]. PS 175 Henry H Garnet (grades PK-5)[174]. PS 185 the Early Childhood Discovery and Design Magnet School (grades PK-2)[175]. PS 194 Countee Cullen (grades PK-5)[176].

PS 197 John B Russwurm (grades PK-5)[177]. PS 200 The James Mccune Smith School (grades PK-5)[178]. PS 242 The Young Diplomats Magnet School (grades PK-5)[179]. Stem Institute of Manhattan (grades K-5)[180].

Thurgood Marshall Academy Lower School (grades K-5)[181]. The following middle and high schools are located in Central Harlem:[168].

Frederick Douglass Academy (grades 6-12)[182]. Frederick Douglass Academy II Secondary School (grades 6-12)[183]. Mott Hall High School (grades 9-12)[184]. Thurgood Marshall Academy For Learning And Social Change (grades 6-12)[185].Wad leigh Secondary School for the Performing and Visual Arts (grades 6-12)[186]. Harlem has a high rate of charter school enrollment: a fifth of students were enrolled in charter schools in 2010. [187] By 2017, that proportion had increased to 36%, about the same that attended their zoned public schools.

Another 20% of Harlem students were enrolled in public schools elsewhere. The CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy, New York College of Podiatric Medicine, City College of New York, and Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine, in addition to a branch of College of New Rochelle, are all located in Harlem. The Morningside Heights and Manhattanville campuses of Columbia University are located just west of Harlem. New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

The New York Public Library (NYPL) operates four circulating branches and one research branch in Harlem, as well as several others in adjacent neighborhoods. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research branch, is located at 515 Malcolm X Boulevard.

It is housed in a Carnegie library structure that opened in 1905, though the branch itself was established in 1925 based on a collection from its namesake, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. The Schomburg Center is a National Historic Landmark, as well as a city designated landmark and a National Register of Historic Places (NRHP)-listed site. The Countee Cullen branch is located at 104 West 136th Street.It was originally housed in the building now occupied by the Schomburg Center. The current structure, in 1941, is an annex of the Schomburg building. The Harry Belafonte 115th Street branch is located at 203 West 115th Street. The three-story Carnegie library, built in 1908, is both a city designated landmark and an NRHP-listed site.

It was renamed for the entertainer and Harlem resident Harry Belafonte in 2017. The Harlem branch is located at 9 West 124th Street. It is one of the oldest libraries in the NYPL system, having operated in Harlem since 1826. The current three-story Carnegie library building was built in 1909 and renovated in 2004. The Macomb's Bridge branch is located at 2633 Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

The branch opened in 1955 at 2650 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, inside the Harlem River Houses, and was the smallest NYPL branch at 685 square feet (63.6 m2). In January 2020, the branch moved across the street to a larger space.

Other nearby branches include the 125th Street and Aguilar branches in East Harlem; the Morningside Heights branch in Morningside Heights; and the George Bruce and Hamilton Grange branches in western Harlem. Bridges spanning the Harlem River between Harlem to the left and the Bronx to the right.

Harlem-125th Street station on the Metro-North Railroad. The Harlem River separates the Bronx and Manhattan, necessitating several spans between the two New York City boroughs.

Five free bridges connect Harlem and the Bronx: the Willis Avenue Bridge (for northbound traffic only), Third Avenue Bridge (for southbound traffic only), Madison Avenue Bridge, 145th Street Bridge, and Macombs Dam Bridge. In East Harlem, the Wards Island Bridge, also known as the 103rd Street Footbridge, connects Manhattan with Wards Island.The Triborough Bridge is a complex of three separate bridges that offers connections between Queens, East Harlem, and the Bronx. Public transportation service is provided by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

This includes the New York City Subway and MTA Regional Bus Operations. Some Bronx local routes also serve Manhattan, providing customers with access between both boroughs. [196][197] Metro-North Railroad has a commuter rail station at Harlem-125th Street, serving trains to the Lower Hudson Valley and Connecticut. Harlem is served by the following subway lines. IRT Lenox Avenue Line 2 and?

3 trains between Central Park North-110th Street and Harlem-148th Street[199]. IND Eighth Avenue Line A, ?D trains between Cathedral Parkway-110th Street and 155th Street[199]. IND Concourse Line B and? D trains at 155th Street[199]. In addition, several other lines stop nearby.

IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line (1 train) between Cathedral Parkway-110th Street and 145th Street, serving western Harlem[199]. IRT Lexington Avenue Line 4, ? Trains between 96th Street and 125th Street, serving East Harlem[199]. Phase 2 of the Second Avenue Subway is also planned to serve East Harlem, with stops at 106th Street, 116th Street, and Harlem-125th Street.

Harlem is served by numerous local bus routes operated by MTA Regional Bus Operations:[197]. Bx6 and Bx6 SBS along 155th Street. M2 along Seventh Avenue, Central Park North, and Fifth/Madison Avenues. M3 along Manhattan Avenue, Central Park North, and Fifth/Madison Avenues. M4 along Broadway, Central Park North, and Fifth/Madison Avenues. M60 SBS, M100, M101 and Bx15 along 125th Street. M7 and M102 along Lenox Avenue and 116th Street. M10 along Frederick Douglass Boulevard. Routes that run near Harlem, but do not stop in the neighborhood, include:[197]. M98 and M103 along Third/Lexington Avenues. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Photographic Images\Photographs". The seller is "memorabilia111" and is located in this country: US.This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay.

- Type: Photograph

- Year of Production: 1944