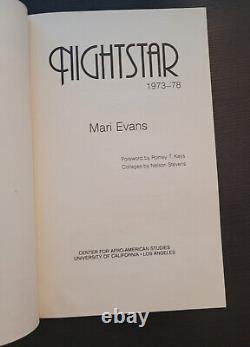

SCARCE SIGNED BOOK Mari Evans African American Poet Black Arts Movement

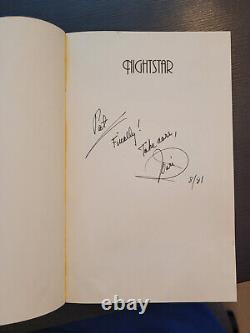

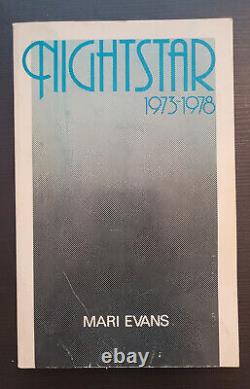

Book Description: Signed by author Mari Evans. Paperback Very gosee I see no signed copies for sale online. Evans received grants and awards including a lifetime achievement award from the Indianapolis Public Library Foundation. Her poetry is known for its lyrical simplicity and the directness of its themes __________________ Mari Evans (July 16, 1919[3][1] - March 10, 2017)[4] was an African-American poet, writer, and dramatist[5] associated with the Black Arts Movement.

[6] Evans received grants and awards including a lifetime achievement award from the Indianapolis Public Library Foundation. Her poetry is known for its lyrical simplicity and the directness of its themes.

Evans died at the age of 97 in Indianapolis, Indiana. [2] Early life and education Evans was born in Toledo, Ohio, on July 16, 1919, to Mary Jane Jacobs and William Reed Evans. [1][7][8] Evans's mother died when Mari was seven years old.[7] Evans's father strongly encouraged her to develop and cultivate her writing ability throughout her life. [9] Evans attended local public schools before enrolling at the University of Toledo in 1939.

She majored in fashion design, but left in 1941 without earning a college degree. [7][9] Career After leaving college, Evans decided to pursue a career as a musician. [7] This decision prompted her to move to the East Coast, where she began to collaborate with various jazz musicians, including Wes Montgomery, a native of Indianapolis, Indiana. In 1947, Evans left the East Coast and moved to Indianapolis.

After she settled in the city, she worked for the Indiana Housing Authority before joining the U. [7][10] Evans gained notoriety as a poet during the 1960s and 1970s and became associated with the Black Arts Movement, [11] an effort to explore African-American culture and history through the arts and literature.

[12] In addition to Evans, other prominent members of the movement were Amiri Baraka, Gwendolyn Brooks, Nikki Giovanni, Etheridge Knight, Haki R. Madhubuti, Larry Neal, and Sonia Sanchez, among others. [13][14] Evans was also an activist interested in social justice issues[15] and a critic of racism. [14] As she later remarked, From the time I was five.I was aware that color was an issue over which the society and I would war. [16] Evans began a series of teaching appointments in American universities in 1969. [7] During 1969-70 she served as writer-in-residence at Indiana University - Purdue University at Indianapolis, where she taught courses in African-American literature. Evans accepted a position the following year as an assistant professor and writer-in-residence at Indiana University in Bloomington, where she taught until 1978.

[5] From 1968 to 1973, Evans produced, wrote, and directed The Black Experience, a weekly television program for WTTV in Indianapolis. [17][18] Later, she explained that the program was her attempt to represent African-Americans to themselves. [6] In 1975 Evans received an honorary doctorate of humane letters degree from Marian College.[19] She continued her teaching career at Purdue University (1978-80), Washington University in St. Louis (1980), Cornell University (1981-85), the State University of New York at Albany (1985-86), and Spelman College. Themes of love, loss, loneliness, struggle, pride, and resistance are common in Evans's poetry.

[5][6][18] She also used "imagery, metaphor, and rhetoric" to describe the African-American experience, the focus of her literary work, [11] and explained that when I write, I write according to the title of poetry Margaret Walker's classic:'for my people'. [20] Evans's writing focused primarily of the issues of race and identity.

Her poems frequently featured African-American women. [21] She also became "known for her intensity and no-nonsense candor". [14] Although her first poetry collection, Where is All the Music?

[21][22] Evans's other memorable poems include: "Celebration", "If There be Sorrow", "Speak the Truth to the People", "When in Rome", and "The Rebel", among others. [21][23] In her later work, Evans began to use experimental techniques and incorporate African-American idioms in ways that encouraged readers to identify with and respect the speaker. [5] Her poems were also characterized as "realistic", "hopeful", "sometimes ironic", and enthusiastic. [14] In her poem "Who Can Be Born Black", she concludes with the lines: Who/ can be born/ black/ and not exhult! [14] In addition, Evans spoke of the need to make Blackness both beautiful and powerful. "[24] She is also well known for the line: "I have never been contained except I made the prison. [citation needed] Although she is primarily known for her poetry, Evans also wrote short fiction, children's books, dramas, nonfiction articles, and essays. [16] Evans tackled social issues in her writing, even in her children's books.Love, Annie (1999), for example, is about child abuse and "I'm Late" (2006) deals with teen pregnancy. [18][25] In 1975 Evans attended the MacDowell Writers Colony and in 1984 she attended the Yaddo writers retreat. [7] Community service Mari Evans was an activist for prison reform, and was against capital punishment. She also worked with theater groups and local community organizations including Girls, Inc.

Of Greater Indianapolis and the Young Men's Christian Association. In addition, Evans volunteered in elementary and secondary schools. [7][26] Personal life Evans, who was divorced and the mother of two sons, led a quiet life in Indianapolis. [15][18] She enjoyed playing the piano and "was a fan of the Indiana Avenue jazz scene" during the 1940s and'50s.

[25] In addition, Evans was a member of Indianapolis's Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, but attended Broadway United Methodist Church in her later years. [14] Death and legacy Evans died in Indianapolis on March 10, 2017, at the age of 97.

[11][27] Funeral services were held at Saint Luke's Methodist Church in Indianapolis due to the large crowd that expected to attend. [14] Evans was "often considered a key figure of the Black Arts Movement" and among the most influential of the twentieth century's black poets. [22] Although she was well known in East Coast "literary circles", Evans and her poetry were not as well known in Indianapolis, where she lived for many years. [15] A literary critic noted that Evans used black idioms to communicate the authentic voice of the black community is a unique characteristic of her poetry.

[21] Selected published works Poetry Where is all the Music? (1973)[19][34] Look at Me!(1974)[19] Rap Stories (1974)[21] Singing Black: Alternative Nursery Rhymes for Children (1976)[19][35] Jim Flying High (1979)[36] Dear Corinne, Tell Somebody! [3] Through activism and art, BAM created new cultural institutions and conveyed a message of black pride. [4] The movement expanded from the accomplishments of artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Famously referred to by Larry Neal as the "aesthetic and spiritual sister of Black Power", [5] BAM applied these same political ideas to art and literature. [6] and artists found new inspiration in their African heritage as a way to present the black experience in America.

Artists such as Aaron Douglas, Hale Woodruff, and Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller pioneered the movement with a distinctly modernist aesthetic. [7] This style influenced the proliferation of African American art during the twentieth century. The poet and playwright Amiri Baraka is widely recognized as the founder of BAM. [8] In 1965, he established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School (BART/S) in Harlem.

[9] Baraka's example inspired many others to create organizations across the United States. [4] While many of these organizations were short-lived, their work has had a lasting influence. Some still exist, including the National Black Theatre, founded by Barabara Ann Teer in Harlem, New York. Background Novelist James Baldwin on the Albert Memorial, Kensington Gardens, London African Americans had always made valuable artistic contributions to American culture.

However, due to brutalities of slavery and the systemic racism of Jim Crow, these contributions often went unrecognized. [10] Despite continued oppression, African-American artists continued to create literature and art that would reflect their experiences.

A high-point for these artists was the Harlem Renaissance-a literary era that spotlighted black people. [11] Harlem Renaissance There are many parallels that can be made between the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement. The link is so strong, in fact, that some scholars refer to the Black Arts Movement era as the Second Renaissance. [12] One sees this connection clearly when reading Langston Hughes's The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain (1926). Hughes's seminal essay advocates that black writers resist external attempts to control their art, arguing instead that the "truly great" black artist will be the one who can fully embrace and freely express his blackness.

[12] Yet, the Harlem Renaissance lacked many of the radical political stances that defined BAM. [13] Inevitably, the Renaissance, and many of its ideas, failed to survive the Great Depression.

[14] Civil Rights Movement During the Civil Rights era, activists paid more and more attention to the political uses of art. The contemporary work of those like James Baldwin and Chester Himes would show the possibility of creating a new'black aesthetic'.A number of art groups were established during this period, such as the Umbra Poets and the Spiral Arts Alliance, which can be seen as precursors to BAM. [15] Art was seen as a way to decompress from the upheaval of the civil rights era by, for example, the ceramicist Marva Lee Pitchford-Jolly, the maker of'Story Pots'.

[16] Civil Rights activists were also interested in creating black-owned media outlets, establishing journals (such as Freedomways, Black Dialogue, The Liberator, The Black Scholar and Soul Book) and publishing houses such as Dudley Randall's Broadside Press and Third World Press. [4] It was through these channels that BAM would eventually spread its art, literature, and political messages. [17][4] Developments The beginnings of the Black Arts Movement may be traced to 1965, when Amiri Baraka, at that time still known as Leroi Jones, moved uptown to establish the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BARTS) following the assassination of Malcolm X. [18] Rooted in the Nation of Islam, the Black Power movement and the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Arts Movement grew out of a changing political and cultural climate in which Black artists attempted to create politically engaged work that explored the African American cultural and historical experience.[19] Black artists and intellectuals such as Baraka made it their project to reject older political, cultural, and artistic traditions. [17] Although the success of sit-ins and public demonstrations of the Black student movement in the 1960s may have "inspired black intellectuals, artists, and political activists to form politicized cultural groups", [17] many Black Arts activists rejected the non-militant integrational ideologies of the Civil Rights Movement and instead favored those of the Black Liberation Struggle, which emphasized self-determination through self-reliance and Black control of significant businesses, organization, agencies, and institutions.

"[20] According to the Academy of American Poets, "African American artists within the movement sought to create politically engaged work that explored the African American cultural and historical experience. The importance that the movement placed on Black autonomy is apparent through the creation of institutions such as the Black Arts Repertoire Theatre School (BARTS), created in the spring of 1964 by Baraka and other Black artists. The opening of BARTS in New York City often overshadow the growth of other radical Black Arts groups and institutions all over the United States. In fact, transgressional and international networks, those of various Left and nationalist (and Left nationalist) groups and their supports, existed far before the movement gained popularity. [17] Although the creation of BARTS did indeed catalyze the spread of other Black Arts institutions and the Black Arts movement across the nation, it was not solely responsible for the growth of the movement.

Although the Black Arts Movement was a time filled with black success and artistic progress, the movement also faced social and racial ridicule. The leaders and artists involved called for Black Art to define itself and speak for itself from the security of its own institutions. For many of the contemporaries the idea that somehow black people could express themselves through institutions of their own creation and with ideas whose validity was confirmed by their own interests and measures was absurd. [21] While it is easy to assume that the movement began solely in the Northeast, it actually started out as "separate and distinct local initiatives across a wide geographic area", eventually coming together to form the broader national movement. [17] New York City is often referred to as the "birthplace" of the Black Arts Movement, because it was home to many revolutionary Black artists and activists.However, the geographical diversity of the movement opposes the misconception that New York (and Harlem, especially) was the primary site of the movement. [17] In its beginning states, the movement came together largely through printed media. Journals such as Liberator, The Crusader, and Freedomways created a national community in which ideology and aesthetics were debated and a wide range of approaches to African-American artistic style and subject displayed. [17] These publications tied communities outside of large Black Arts centers to the movement and gave the general black public access to these sometimes exclusive circles. As a literary movement, Black Arts had its roots in groups such as the Umbra Workshop.

Umbra (1962) was a collective of young Black writers based in Manhattan's Lower East Side; major members were writers Steve Cannon, [22] Tom Dent, Al Haynes, David Henderson, Calvin C. Hernton, Joe Johnson, Norman Pritchard, Lennox Raphael, Ishmael Reed, Lorenzo Thomas, James Thompson, Askia M. Touré (Roland Snellings; also a visual artist), Brenda Walcott, and musician-writer Archie Shepp. Touré, a major shaper of "cultural nationalism", directly influenced Jones.

Along with Umbra writer Charles Patterson and Charles's brother, William Patterson, Touré joined Jones, Steve Young, and others at BARTS. Umbra, which produced Umbra Magazine, was the first post-civil rights Black literary group to make an impact as radical in the sense of establishing their own voice distinct from, and sometimes at odds with, the prevailing white literary establishment. The attempt to merge a black-oriented activist thrust with a primarily artistic orientation produced a classic split in Umbra between those who wanted to be activists and those who thought of themselves as primarily writers, though to some extent all members shared both views. Black writers have always had to face the issue of whether their work was primarily political or aesthetic.

Moreover, Umbra itself had evolved out of similar circumstances: in 1960 a Black nationalist literary organization, On Guard for Freedom, had been founded on the Lower East Side by Calvin Hicks. Its members included Nannie and Walter Bowe, Harold Cruse (who was then working on The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, 1967), Tom Dent, Rosa Guy, Joe Johnson, LeRoi Jones, and Sarah E. On Guard was active in a famous protest at the United Nations of the American-sponsored Bay of Pigs Cuban invasion and was active in support of the Congolese liberation leader Patrice Lumumba. From On Guard, Dent, Johnson, and Walcott along with Hernton, Henderson, and Touré established Umbra. In 1967, the Visual Arts Workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture, composed of several artists such as Jeff Donaldson, William Walker, and more, painted the Wall of Respect which was a mural that represented the Black Arts Movement; what it stood for and who it was celebrating.The mural commemorated several important black figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. And Malcolm X, along with artists such as Aretha Franklin and Gwendolyn Brooks, etc. [23] It was a renowned symbol of the movement, placed in Chicago, that represented black culture and creativity, and was met with a lot of attention, support, and respect from the black community. It was a symbolic and important representation of the Black Arts Movement, as it directly celebrated and acknowledged the iconic figures of the Black community through art, emphasizing the importance of art for the community.

Furthermore, it left a legacy and served as a beacon for the Black community, promoting Black consciousness and helping many Black people to learn and recognize their worth. In the eight years following the installation of the mural, over 1,500 murals were painted in black neighborhoods across the country, and by 1975, over 200 were painted in Chicago. It brought the community together symbolically, and literally, as rival gangs even declared the location of the mural to be neutral ground, supporting the artists and the movement. [24] In 1968, renowned Black theorist Barbara Ann Teer founded the National Black Theatre, located in Harlem, New York. Teer was an American writer, producer, teacher, actress and social visionary.

Teer was an important black female intellectual, artist, and activist who contributed to the Black Arts Movement. Her theater was one of the first revenue generating Black theaters in the US. Teer's art was politically and socially conscious and like many other contributors to the BAM, embraced African aesthetics, and rejected traditional theatrical notions of time and space. Teer's revolutionary and ritualistic dramas and plays blurred the lines between performers and audience, encouraging all to use the performance event itself as an opportunity to bring about social change. Authors Another formation of black writers at that time was the Harlem Writers Guild, led by John O.

Killens, which included Maya Angelou, Jean Carey Bond, Rosa Guy, and Sarah Wright among others. But the Harlem Writers Guild focused on prose, primarily fiction, which did not have the mass appeal of poetry performed in the dynamic vernacular of the time. Poems could be built around anthems, chants, and political slogans, and thereby used in organizing work, which was not generally the case with novels and short stories.

Moreover, the poets could and did publish themselves, whereas greater resources were needed to publish fiction. That Umbra was primarily poetry- and performance-oriented established a significant and classic characteristic of the movement's aesthetics. When Umbra split up, some members, led by Askia Touré and Al Haynes, moved to Harlem in late 1964 and formed the nationalist-oriented Uptown Writers Movement, which included poets Yusef Rahman, Keorapetse "Willie" Kgositsile from South Africa, and Larry Neal. Accompanied by young "New Music" musicians, they performed poetry all over Harlem.

Members of this group joined LeRoi Jones in founding BARTS. Jones's move to Harlem was short-lived. , and left BARTS in serious disarray.BARTS failed but the Black Arts center concept was irrepressible, mainly because the Black Arts movement was so closely aligned with the then-burgeoning Black Power movement. The mid-to-late 1960s was a period of intense revolutionary ferment. Beginning in 1964, rebellions in Harlem and Rochester, New York, initiated four years of long hot summers.

Watts, Detroit, Newark, Cleveland, and many other cities went up in flames, culminating in nationwide explosions of resentment and anger following the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Nathan Hare, author of The Black Anglo-Saxons (1965), was the founder of 1960s Black Studies. Expelled from Howard University, Hare moved to San Francisco State University, where the battle to establish a Black Studies department was waged during a five-month strike during the 1968-69 school year. As with the establishment of Black Arts, which included a range of forces, there was broad activity in the Bay Area around Black Studies, including efforts led by poet and professor Sarah Webster Fabio at Merrit College. The initial thrust of Black Arts ideological development came from the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), a national organization with a strong presence in New York City. Both Touré and Neal were members of RAM. After RAM, the major ideological force shaping the Black Arts movement was the US (as opposed to "them") organization led by Maulana Karenga. Also ideologically important was Elijah Muhammad's Chicago-based Nation of Islam. These three formations provided both style and conceptual direction for Black Arts artists, including those who were not members of these or any other political organization. Although the Black Arts Movement is often considered a New York-based movement, two of its three major forces were located outside New York City.Locations As the movement matured, the two major locations of Black Arts' ideological leadership, particularly for literary work, were California's Bay Area because of the Journal of Black Poetry and The Black Scholar, and the Chicago-Detroit axis because of Negro Digest/Black World and Third World Press in Chicago, and Broadside Press and Naomi Long Madgett's Lotus Press in Detroit. Although the journals and writing of the movement greatly characterized its success, the movement placed a great deal of importance on collective oral and performance art. Public collective performances drew a lot of attention to the movement, and it was often easier to get an immediate response from a collective poetry reading, short play, or street performance than it was from individual performances. [17] The people involved in the Black Arts Movement used the arts as a way to liberate themselves. The movement served as a catalyst for many different ideas and cultures to come alive.

This was a chance for African Americans to express themselves in a way that most would not have expected. In 1967, LeRoi Jones visited Karenga in Los Angeles and became an advocate of Karenga's philosophy of Kawaida. Kawaida, which produced the "Nguzo Saba" (seven principles), Kwanzaa, and an emphasis on African names, was a multifaceted, categorized activist philosophy. Jones also met Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver and worked with a number of the founding members of the Black Panthers. Additionally, Askia Touré was a visiting professor at San Francisco State and was to become a leading (and long-lasting) poet as well as, arguably, the most influential poet-professor in the Black Arts movement. Playwright Ed Bullins and poet Marvin X had established Black Arts West, and Dingane Joe Goncalves had founded the Journal of Black Poetry (1966). [25] This grouping of Ed Bullins, Dingane Joe Goncalves, LeRoi Jones, Sonia Sanchez, Askia M. Touré, and Marvin X became a major nucleus of Black Arts leadership.[26] As the movement grew, ideological conflicts arose and eventually became too great for the movement to continue to exist as a large, coherent collective. The Black Aesthetic Part of a series on African Americans History Culture Religion Politics Civic/economic groups Sports Sub-communities Dialects and languages Population Prejudice flag United States portal Category Index vte Although The Black Aesthetic was first coined by Larry Neal in 1968, across all the discourse, The Black Aesthetic has no overall real definition agreed by all Black Aesthetic theorists. [27] It is loosely defined, without any real consensus besides that the theorists of The Black Aesthetic agree that "art should be used to galvanize the black masses to revolt against their white capitalist oppressors". [28] Pollard also argues in her critique of the Black Arts Movement that The Black Aesthetic "celebrated the African origins of the Black community, championed black urban culture, critiqued Western aesthetics, and encouraged the production and reception of black arts by black people".

In The Black Arts Movement by Larry Neal, where the Black Arts Movement is discussed as "aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept", The Black Aesthetic is described by Neal as being the merge of the ideologies of Black Power with the artistic values of African expression. [29] Larry Neal attests: When we speak of a'Black aesthetic' several things are meant.First, we assume that there is already in existence the basis for such an aesthetic. Essentially, it consists of an African-American cultural tradition. But this aesthetic is finally, by implication, broader than that tradition. It encompasses most of the usable elements of the Third World culture. The motive behind the Black aesthetic is the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the world.

[30] The Black Aesthetic also refers to ideologies and perspectives of art that center on Black culture and life. This Black Aesthetic encouraged the idea of Black separatism, and in trying to facilitate this, hoped to further strengthen black ideals, solidarity, and creativity.

[31] In The Black Aesthetic (1971), Addison Gayle argues that Black artists should work exclusively on uplifting their identity while refusing to appease white folks. [32] The Black Aesthetic work as a "corrective", where black people are not supposed to desire the "ranks of Norman Mailer or a William Styron".

[27] Black people are encouraged by Black artists that take their own Black identity, reshaping and redefining themselves for themselves by themselves via art as a medium. [33] Hoyt Fuller defines The Black Aesthetic "in terms of the cultural experiences and tendencies expressed in artist' work"[27] while another meaning of The Black Aesthetic comes from Ron Karenga, who argues for three main characteristics to The Black Aesthetic and Black art itself: functional, collective, and committing. Karenga says, "Black Art must expose the enemy, praise the people, and support the revolution". The notion "art for art's sake" is killed in the process, binding the Black Aesthetic to the revolutionary struggle, a struggle that is the reasoning behind reclaiming Black art in order to return to African culture and tradition for Black people.

[34] Under Karenga's definition of The Black Aesthetic, art that does not fight for the Black Revolution is not considered as art at all, needed the vital context of social issues as well as an artistic value. Among these definitions, the central theme that is the underlying connection of the Black Arts, Black Aesthetic, and Black Power movements is then this: the idea of group identity, which is defined by Black artists of organizations as well as their objectives. [32] The narrowed view of The Black Aesthetic, often described as Marxist by critics, brought upon conflicts of the Black Aesthetic and Black Arts Movement as a whole in areas that drove the focus of African culture;[35] In The Black Arts Movement and Its Critics, David Lionel Smith argues in saying "The Black Aesthetic", one suggests a single principle, closed and prescriptive in which just really sustains the oppressiveness of defining race in one single identity.

[27] The search of finding the true "blackness" of Black people through art by the term creates obstacles in achieving a refocus and return to African culture. Smith compares the statement "The Black Aesthetic" to "Black Aesthetics", the latter leaving multiple, open, descriptive possibilities.

The Black Aesthetic, particularly Karenga's definition, has also received additional critiques; Ishmael Reed, author of Neo-HooDoo Manifesto, argues for artistic freedom, ultimately against Karenga's idea of the Black Aesthetic, which Reed finds limiting and something he cannot ever sympathize to. [36] The example Reed brings up is if a Black artist wants to paint black guerrillas, that is okay, but if the Black artist "does so only deference to Ron Karenga, something's wrong". [36] The focus of blackness in context of maleness was another critique raised with the Black Aesthetic.

[28] Pollard argues that the art made with the artistic and social values of the Black Aesthetic emphasizes on the male talent of blackness, and it is uncertain whether the movement only includes women as an afterthought. As there begins a change in the Black population, Trey Ellis points out other flaws in his essay "The New Black Aesthetic". [37] Blackness in terms of cultural background can no longer be denied in order to appease or please white or black people. From mulattos to a "post-bourgeois movement driven by a second generation of middle class", blackness is not a singular identity as the phrase "The Black Aesthetic" forces it to be but rather multifaceted and vast. [37] BAM also turned to the religious tradition of voodoo in defining black aesthetics. James Baldwin was critical of both the black church and Nation of Islam. He argued that Christianity had only been forced on black people to rationalize and justify slavery and colonization. Nation of Islam failed in its strong mission to separate itself and black people from white people, said Baldwin, especially looking at their culture of expensive suits and cars all the while demonizing white people. Voodoo then became an alternative to Christianity and Islam for BAM.The historical tradition of voodoo among enslaved Africans had been forgotten in favor of assimilation to the white, Christian identity. The turn to voodoo is therefore regardes as a pan-African reclaiming of the roots.

The approximation to voodoo is maybe most clear in the poetry collection "Hoodoo Hollerin Bebop Ghosts" by Larry Neal and the novels "Neo-Hoo-Doo Manifesto" and "Mumbo Jumbo" by Ishmael Reed. [38] Major works Black Art Amiri Baraka's poem "Black Art" serves as one of his more controversial, poetically profound supplements to the Black Arts Movement. In this piece, Baraka merges politics with art, criticizing poems that are not useful to or adequately representative of the Black struggle.

First published in 1966, a period particularly known for the Civil Rights Movement, the political aspect of this piece underscores the need for a concrete and artistic approach to the realistic nature involving racism and injustice. Serving as the recognized artistic component to and having roots in the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Arts Movement aims to grant a political voice to black artists including poets, dramatists, writers, musicians, etc. Playing a vital role in this movement, Baraka calls out what he considers to be unproductive and assimilatory actions shown by political leaders during the Civil Rights Movement. He describes prominent Black leaders as being on the steps of the white house... Kneeling between the sheriff's thighs negotiating coolly for his people. Baraka also presents issues of euro-centric mentality, by referring to Elizabeth Taylor as a prototypical model in a society that influences perceptions of beauty, emphasizing its influence on individuals of white and black ancestry. Baraka aims his message toward the Black community, with the purpose of coalescing African Americans into a unified movement, devoid of white influences."Black Art" serves as a medium for expression meant to strengthen that solidarity and creativity, in terms of the Black Aesthetic. Baraka believes poems should shoot... Come at you, love what you are and not succumb to mainstream desires.

[39] He ties this approach into the emergence of hip-hop, which he paints as a movement that presents live words... And live flesh and coursing blood. "[39] Baraka's cathartic structure and aggressive tone are comparable to the beginnings of hip-hop music, which created controversy in the realm of mainstream acceptance, because of its "authentic, un-distilled, unmediated forms of contemporary black urban music.

[40] Baraka believes that integration inherently takes away from the legitimacy of having a Black identity and Aesthetic in an anti-Black world. Through pure and unapologetic blackness, and with the absence of white influences, Baraka believes a black world can be achieved. Though hip-hop has been serving as a recognized salient musical form of the Black Aesthetic, a history of unproductive integration is seen across the spectrum of music, beginning with the emergence of a newly formed narrative in mainstream appeal in the 1950s. Much of Baraka's cynical disillusionment with unproductive integration can be drawn from the 1950s, a period of rock and roll, in which "record labels actively sought to have white artists "cover" songs that were popular on the rhythm-and-blues charts"[40] originally performed by African-American artists.

The problematic nature of unproductive integration is also exemplified by Run-DMC, an American hip-hop group founded in 1981, who became widely accepted after a calculated collaboration with the rock group Aerosmith on a remake of the latter's "Walk This Way" took place in 1986, evidently appealing to young white audiences. [40] Hip-hop emerged as an evolving genre of music that continuously challenged mainstream acceptance, most notably with the development of rap in the 1990s. A significant and modern example of this is Ice Cube, a well-known American rapper, songwriter, and actor, who introduced subgenre of hip-hop known as "gangsta rap", merged social consciousness and political expression with music. With the 1960s serving as a more blatantly racist period of time, Baraka notes the revolutionary nature of hip-hop, grounded in the unmodified expression through art. This method of expression in music parallels significantly with Baraka's ideals presented in "Black Art", focusing on poetry that is also productively and politically driven. The Revolutionary Theatre "The Revolutionary Theatre" is a 1965 essay by Baraka that was an important contribution to the Black Arts Movement, discussing the need for change through literature and theater arts.He says: We will scream and cry, murder, run through the streets in agony, if it means some soul will be moved, moved to actual life understanding of what the world is, and what it ought to be. Baraka wrote his poetry, drama, fiction and essays in a way that would shock and awaken audiences to the political concerns of black Americans, which says much about what he was doing with this essay. [41] It also did not seem coincidental to him that Malcolm X and John F. Kennedy had been assassinated within a few years because Baraka believed that every voice of change in America had been murdered, which led to the writing that would come out of the Black Arts Movement.

In his essay, Baraka says: The Revolutionary Theatre is shaped by the world, and moves to reshape the world, using as its force the natural force and perpetual vibrations of the mind in the world. We are history and desire, what we are, and what any experience can make us. With his thought-provoking ideals and references to a euro-centric society, he imposes the notion that black Americans should stray from a white aesthetic in order to find a black identity. In his essay, he says: The popular white man's theatre like the popular white man's novel shows tired white lives, and the problems of eating white sugar, or else it herds bigcaboosed blondes onto huge stages in rhinestones and makes believe they are dancing or singing. " This, having much to do with a white aesthetic, further proves what was popular in society and even what society had as an example of what everyone should aspire to be, like the "bigcaboosed blondes" that went "onto huge stages in rhinestones.

Furthermore, these blondes made believe they were "dancing and singing" which Baraka seems to be implying that white people dancing is not what dancing is supposed to be at all. These allusions bring forth the question of where black Americans fit in the public eye.

Baraka says: We are preaching virtue and feeling, and a natural sense of the self in the world. All men live in the world, and the world ought to be a place for them to live.

Baraka's essay challenges the idea that there is no space in politics or in society for black Americans to make a difference through different art forms that consist of, but are not limited to, poetry, song, dance, and art. Effects on society Ntozake Shange (1978), author of for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf According to the Academy of American Poets, many writers-Native Americans, Latinos/as, gays and lesbians, and younger generations of African Americans have acknowledged their debt to the Black Arts Movement. [19] The movement lasted for about a decade, through the mid-1960s and into the 1970s.This was a period of controversy and change in the world of literature. One major change came through in the portrayal of new ethnic voices in the United States. English-language literature, prior to the Black Arts Movement, was dominated by white authors.

[42] African Americans became a greater presence not only in the field of literature but in all areas of the arts. Theater groups, poetry performances, music and dance were central to the movement.

Through different forms of media, African Americans were able to educate others about the expression of cultural differences and viewpoints. In particular, black poetry readings allowed African Americans to use vernacular dialogues. This was shown in the Harlem Writers Guild, which included black writers such as Maya Angelou and Rosa Guy. These performances were used to express political slogans and as a tool for organization.

Theater performances also were used to convey community issues and organizations. The theaters, as well as cultural centers, were based throughout America and were used for community meetings, study groups and film screenings. Newspapers were a major tool in spreading the Black Arts Movement. In 1964, Black Dialogue was published, making it the first major Arts movement publication. The Black Arts Movement, although short, is essential to the history of the United States.

It spurred political activism and use of speech throughout every African-American community. It allowed African Americans the chance to express their voices in the mass media as well as become involved in communities.It can be argued that "the Black Arts movement produced some of the most exciting poetry, drama, dance, music, visual art, and fiction of the post-World War II United States" and that many important "post-Black artists" such as Toni Morrison, Ntozake Shange, Alice Walker, and August Wilson were shaped by the movement. [17] The Black Arts Movement also provided incentives for public funding of the arts and increased public support of various arts initiatives.

[17] Legacy The movement has been seen as one of the most important times in African-American literature. It inspired black people to establish their own publishing houses, magazines, journals and art institutions. It led to the creation of African-American Studies programs within universities. [43] Some claim that the movement was triggered by the assassination of Malcolm X, but its roots predate that event.

[18] Among the well-known writers who were involved with the movement are Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, Maya Angelou, Hoyt W. [44][45] Although not strictly part of the Movement, other notable African American writers such as Toni Morrison, Jay Wright, and Ishmael Reed share some of its artistic and thematic concerns.Although Reed is neither a movement apologist nor advocate, he said: I think what Black Arts did was inspire a whole lot of Black people to write. Moreover, there would be no multiculturalism movement without Black Arts.

Latinos, Asian Americans, and others all say they began writing as a result of the example of the 1960s. Blacks gave the example that you don't have to assimilate. You could do your own thing, get into your own background, your own history, your own tradition and your own culture. I think the challenge is for cultural sovereignty and Black Arts struck a blow for that. [46] BAM influenced the world of literature with the portrayal of different ethnic voices. Before the movement, the literary canon lacked diversity, and the ability to express ideas from the point of view of racial and ethnic minorities, which was not valued by the mainstream at the time. BAM also spurred experimentalism in Black letters.[47] Influence Theater groups, poetry performances, music and dance were centered on this movement, and therefore African Americans gained social and historical recognition in the area of literature and arts. Due to the agency and credibility given, African Americans were also able to educate others through different types of expressions and media outlets about cultural differences. The most common form of teaching was through poetry reading. African-American performances were used for their own political advertisement, organization, and community issues. The Black Arts Movement was spread by the use of newspaper advertisements.

[1] The first major arts movement publication was in 1964. [19] Notable individuals Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) Larry Neal Nikki Giovanni Maya Angelou Gwendolyn Brooks Haki R. Madhubuti (formerly Don Lee) Sun Ra Audre Lorde James Baldwin Hoyt W.

Fuller Ishmael Reed Rosa Guy Dudley Randall Ed Bullins David Henderson Henry Dumas Sonia Sanchez Faith Ringgold Ming Smith Betye Saar Cheryl Clarke John Henrik Clarke Jayne Cortez Don Evans Mari Evans Sarah Webster Fabio Wanda Coleman Barbara Ann Teer Askia M. Touré Marvin X Ossie Davis June Jordan Sarah E. Wright Amina Baraka (formerly Sylvia Robinson) Ellis Haizlip David Hammons Eugene "Eda" Wade Notable organisations AfriCOBRA Black Academy of Arts and Letters Black Artists Group Black Arts Repertory Theatre School Black Dialogue Black Emergency Cultural Coalition Broadside Press Freedomways Harlem Writers Guild National Black Theatre Negro Digest Organization of Black American Culture Soul Book Soul! The Black Scholar The Crusader The Liberator Uptown Writers Movement Mari Evans Indianapolis, Marion County July 16, 1923 - March 10, 2017 Mari Evans was born in Toledo, Ohio.

After her mother died when Mari was 10 year old, her father encouraged her to write. After attending local public schools, Mari Evans enrolled at the University of Toledo where she majored in fashion design; however, she left before receiving a degree. An Indianapolis resident since 1947, she became a famed poet during the Black Arts Movement during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1969, she began teaching at universities throughout the United States.Her first assignment was as writer-in-residence at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis. Among other universities, she taught at Indiana University-Bloomington, Cornell University, and Spellman College. Renowned for her poetry on the African-American experience, Mari Evans also wrote short stories, children's books, theater pieces, and non-fiction articles. One of her best known poems, "When in Rome, " has been taught in many high schools and college English classes.

Despite national recognition and many honors for her contributions to the literary world, her work was not well-known to many in her hometown. However, in recent years, community members who were moved by her work strove to change that. In August 2016, she was honored with a 30-foottall mural by Michael "Alkemi" Jordon located on Mass Ave in downtown Indianapolis.

Later that year, an art exhibit opened in Indianapolis celebrating her work as an example of the strength and significance of black culture. Mari Evans died in Indianapolis on March 10, 2017. Her poem, "The Rebel" pays tribute to her adeptness, humor, and wisdom: When I die I'm sure I will have a Big Funeral...Or just trying to make Trouble. Mari Evans, a Black educator and writer, was born on this date in 1923.

She was born in Toledo, Ohio, and raised in a traditional Black family. She attended the University of Toledo. Evans pursued a career in teaching, lecturing on literature, and writing in several schools in the Midwest and East, including Indiana University, Purdue, and Spelman College. Evans wrote, produced, and directed a television program called "The Black Experience" for an Indianapolis television station.

She has won many awards for her poetry, including the Indiana University Writers' Conference award and the Black Academy of Arts and Letters' first annual African American educator and writer poetry award. Evans wrote a play, "River of My Song, " which was produced in 1977, and in 1979, the musical "Eyes, " an adaptation of Zora Neale Hurston's book, Their Eyes Were Watching God. She is also the editor of other literature collections. Some of her poetry, "A Hand Is on the Gate" and "Walk Together Children, " have been choreographed and used on record albums, filmstrips, and off-Broadway productions.

Evans resides in Indianapolis and is an assistant professor at Cornell University. She is the author of numerous articles and five children's books, and her work has been included in more than 400 anthologies and textbooks. Mari Evans was born in Toledo, Ohio, on July 16, 1923. Her father encouraged her writing by saving her first story, which Evans had written in the fourth grade and then printed in her school newspaper. Evans recounted the experience in her autobiographical essay, "My Father's Passage" (1984).

She studied fashion design at the University of Toledo before focusing on poetry. While working as an assistant editor at a manufacturing firm, she honed her craft. Evans's books for children include Dear Corinne, Tell Somebody! Love, Annie: A Book about Secrets (Just Us Books, 1999); Singing Black: Alternative Nursery Rhymes for Children (Just Us Books, 1998), illustrated by Ramon Price; Jim Flying High (Doubleday, 1979), illustrated by Ashley Bryan; and J.

(Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1973), illustrated by Jerry Pinkney. She was also the author of the plays Eye, a 1979 adaptation of Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God, and River of My Song, which was first produced in 1977.

Among Evans's honors are fellowships from MacDowell, Yaddo, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Evans taught at numerous colleges and universities, including Spelman College, Purdue University, and Cornell. She was also an activist, deeply involved in prison reform, community organizing, and efforts to end capital punishment. Evans lived in Indianapolis from 1947 until her death. She died on March 10, 2017.Her friends and contemporaries, Sonia Sanchez and Nikki Giovanni, spoke at her funeral service. Black man running Thru the ageless sun and shadow History repeated past all logic Who is it bides the time and why? -Mari Evans, "Alabama Landscape" Mari Evans, born 90 years ago today in Toledo, moved to Indianapolis as a young adult. Poet, elder, activist, and editor of one of the first critical volumes devoted to Black women writers, Evans has been celebrating blackness and speaking truth to power throughout her distinguished career.

In light of the George Zimmerman verdict this week, I've been reading and rereading Ms. I know poetry will not resurrect Trayvon Martin or Emmett Till or Michael Taylor, the 17-year-old who allegedly "committed suicide" in the backseat of an Indianapolis squad car while his hands were cuffed behind his back. But Evans' crisp mind-her way of stating, as she once said, "the Truths that are part of my pulse"-illuminates what some would shroud in mystification ("Ethos and Creativity" 28).

And that light of consciousness can provide a way forward. Look / on me and be / renewed (12).

Like Angelina Weld Grimké's "Tenebris, " with its cypress likened to a "black finger / Pointing upwards, " Evans' poem renders the tall, thin, elegant tree an emblem of uplift and aspiration. If one way of suggesting a consciousness both personal and communal is to use a first-person, trans-historical narrator, another way is to write a series of persona poems that give voice to a chorus of black women. For example, in the ironically titled "When in Rome, " the domestic worker Mattie is told by her employer: the box is full / take / whatever you like to eat. But Mattie is less than thrilled with the woman's endive and cottage cheese. If I had some / black-eyed peas.

Rather like the Hattie Scott character in a suite of poems by Gwendolyn Brooks, Mattie's lines-in parentheses-suggest the subversive activity of a free mind at work, even if those thoughts don't get uttered aloud. Born and raised in Toledo, Ohio, Black Arts poet, playwright, and children's writer Mari Evans was educated at the University of Toledo, where she studied fashion design. She was influenced by Langston Hughes, who was an early supporter of her writing. In her short-lined poems, grounded in personal narratives, Evans explored the nature of community and the power of language to name and reframe.

Evans also published the essay collection Clarity as Concept: A Poet's Perspective (2006). In her essay "How We Speak, " published in Clarity as Concept, Evans wrote, Listening is a special art. It is a fine art developed by practice. One hears the unexpressed as clearly as if it had been verbalized.

One hears silence screaming in clarion tones. Hears hunger gnawing at the back of spines; hears aching feet pushed past that one more step.

Hears the repressed hurt of incest, hears the anguish of spousal abuse. Clearly, listening is a fine art. It can translate an obscure text into reality that walks, weeps and carries its own odor. Listening can decode a stranger's eye and hear autobiography. Listening can watch a listless babe and understand the absence of future, the improbability, in fact, of possibility.

Listening, more often than not, is a crushing experience. Evans's books for younger audiences include I'm Late: The Story of LaNeese and Moonlight and Alisha Who Didn't Have Anyone of Her Own (2006); Dear Corinne, Tell Somebody! Love, Annie: A Book About Secrets (1999); Singing Black: Alternative Nursery Rhymes for Children (1998, illustrated by Ramon Price); Jim Flying High (1979, illustrated by Ashley Bryan); and J. (1973, illustrated by Jerry Pinkney).

Evans's plays include Boochie (1979), Portrait of a Man (1979), River of My Song (1977), and the musicals New World (1984) and Eye (1979, an adaptation of Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God). Her work featured in numerous anthologies, including Black Voices: An Anthology of Afro-American Literature (1968) and Black Out Loud: An Anthology of Modern Poems by Black Americans (1970). She taught at Spelman College, Purdue University, and Cornell University. Evans lived in Indianapolis for nearly 70 years, before her death in 2017.

For nearly 70 years, Indiana was home to "one of the founders of the Black Arts Movement, " Mari Evans. [1] While Evans' poetry is known worldwide, she also earned a reputation as a playwright, composer, musician, author, and activist whose work has been anthologized in over 400 collections. [2] Evans' work often tackled subjects such as racial and gender disparities both in Indianapolis and throughout greater society. [3] She was writer-in-residence and an assistant professor at both IUPUI and IU Bloomington and used her affiliation with IU to urge social progress in numerous Hoosier communities. [4] Early Education and Life Mari Evans was born on July 16, 1923 in Toledo, OH. [5] Her mother died when Evans was a young child. During her youth, her father encouraged her to begin writing. [6] In 1939, she enrolled at the University of Toledo to pursue fashion design.However, Evans dropped out of the university in 1941 to pursue a career in jazz. She first moved to the East Coast, where she performed with jazz musicians such as Wes Montgomery, an Indianapolis native. Evans moved to Indianapolis in 1947, where she remained for the rest of her life.

[7] When Evans arrived in Indianapolis in 1947, she worked a variety of different jobs. During the 1950s she worked with the Indiana Housing Authority and the U.

Evans became a dominant figure in the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s. [8] Coming to Indiana University Evans began working for Indiana University in 1969, when she was appointed as writer-in-residence at IUPUI. [9] She taught courses such as "Black Literature: An Overview" and "Recent Black American Writing, " as well as a seminar called Black Literary Tradition. [10] The Black Student Union protesting discriminatory racial practices on the IUPUI campus, 1971. Courtesy of IUPUI Special Collections and Archives During her time at IUPUI, Evans worked closely with the Black Student Union, which some considered to be "the most significant organization on campus" at the time.

[11] In March 1970, she helped the group organize a "Black Celebration" which recognized the contributions of people of color to the arts and other facets of society. Taylor, dean of IUPUI from 1967-70, acknowledged Evans' contribution to the event, With the expert help of Indianapolis poet Mari Evans, our writer-in-residence, the students [of the Black Student Union] have organized an impressive program. [12] In 1971, Evans began work at IU Bloomington as a writer-in-residence and assistant professor of African American Studies. She taught courses such as Early and Contemporary Black Literature and Poetry. [13] She also taught at other universities during this decade, including Northwestern University (1972-73) and Purdue University (1978-80).

[14] Despite her fame as a writer, Evans felt apprehensive about teaching writing courses to college students for fear of tampering with the natural creative flow of another human being. [15] An undated photo of Mari Evans. Courtesy of Emory University Special Collections and Archives While Evans was at IUPUI she became close friends with William Plater. They co-taught a course called "Social Uses of Literature, " in which students read some of Evans' work. The course was intended to help "shape cultural understanding" about social and racial issues.

[16] In this course, Evans combined her passions for writing and political activity as she demonstrated her commitment to the university. Plater stated that she was "very generous with her time" at IUPUI, while holding the campus accountable for the social grievances that the Indianapolis Black community experienced. [17] Although Evans left IU in 1978, her contribution to the university community transcended her official time as a professor. Using her skills as a playwright, she collaborated with David Baker, a renowned jazz professor, and William C. Banfield, a former professor of African-American Studies and Music, to create "Eyes, " a musical adaptation of Zora Neale Hurston's novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. [18] While Baker and Banfield were responsible for the orchestration and arrangement, Evans composed the script, music, and lyrics. [19] Sponsored by IUPUI, the musical premiered in 1994 at the American Cabaret Theatre in Indianapolis. [20] IUPUI used this production to connect with the Indianapolis community, creating an opportunity to talk about the crucial topics of racism, sexism, poverty and hope in a way that does not require recrimination or political double-talk. "[21] A program cover of "Eyes, which was performed in 1995. Courtesy of IUPUI Special Collections and Archives "IUPUI is the public's place of concourse for the discussion and resolution of difficult issues.'Eyes' may have been the best way for Indianapolis to talk about such sensitive but vital subjects, " Plater stated in 1995 after the production finished. [22] Evans continued her commitment to IU through creating a scholarship to help IUPUI students with artistic talent.Created in 1996, the Zora Neale Hurston-Mari Evans Scholarship, is awarded to at least five currently enrolled IUPUI students yearly. [23] Mari Evans with Zora Neale Hurston-Mari Evans Scholarship recipients, 2011[24] Important Works During her time at IU and IUPUI, Evans created some of her most famous works of art. From 1968-73, she wrote, produced, and directed a TV documentary called "The Black Experience" which aired during prime time in Indianapolis which is where Evans she had lived her own Black Experience. [25] David Baker worked together with Evans to create a musical score for the program. [26] Other works during this time included the books J.

(1973) and Singing Black (1976). [27] Although these works often addressed racial issues, her commentary included other difficult topics such as child abuse (Boochie, 1979) and teenage pregnancy (I'm Late, 2006). [28] Evans was especially invested in the issue of the housing displacement of the Black community in Indianapolis, which she wrote about in "Where We Live: Essays About Indiana" in Ethos and Creativity (1989). [29] She wrote, What we find is that racism, in this up-South city at the end of the twentieth century, is like a steel strand encased in nylon then covered in some luxurious fabric. The intent is to avoid, if possible, blatant offenses, to soothe, mollify, if necessary, dissemble-while racism, the steel strand, still effectively does the job. Part of her first collection of poetry, it won the Black Academy of Arts and Letters poetry award. In Qatar in April 2018, the Virginia Commonwealth University opened an exhibit featuring her life. Courtesy of Blackpast reference center Around Indianapolis, there are numerous homages to her, including a 30-foot mural painted by artist Michael Alkemi Jordan in 2016. During the recognition ceremony for her mural, August 13 was declared "Mari Evans Day" in the city to recognize her influence.[31] Evans at the dedication of her mural at the Athenaeum in Indianapolis on August 13, 2016. Courtesy of the Indianapolis Star Indiana has also recognized Evans' influence on the state, its cities, and its institutions. The Indiana Historical Society honored Evans as a "living legend" in 2004 and she received the Indiana Authors Award Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018. [32] During her affiliation with IU, Evans received dozens of awards. She won the Indiana University Writers' Conference Award in 1970.

[33] She also received IUPUI's highest honor, an honorary doctorate degree, in 2000; she was one of the three people who earned the honor on the IUPUI campus that year. [34] The mural of Evans on Massachusetts Avenue in Indianapolis.Courtesy of the Indianapolis Star, August 13, 2016 Her friend and former colleague William Plater, IUPUI dean of the faculties emeritus and the executive vice chancellor of IUPUI, nominated her for this honor due to her contributions to campus and the international impact of her work. [35] Evans composed one of the six poems that are featured on "The Indiana Windows, " a set of glass murals in the Indianapolis International Airport. [36] This poem, "Celebration, " is one of the ways that Evans wanted herself to be remembered.

[37] I will bring you a whole person And you will bring me a whole person And we will have us twice as much Of love and everything[38] Evans died on March 10, 2017 in Indianapolis at the age of 97, although many reports incorrectly stated that she died at the age of 93. [39] Mari Evans helped expose inequalities in Indiana and society as a whole through her insightful writing and other work throughout her legendary life. [40] In one of her last interviews in 2017, Evans talks about her life's work, Well, all I ever really tried to do is speak the truth. I think I can say that everything I've ever written has been an effort to speak with integrity and to say things I feel are genuinely true. Listen, I think I'm a stand-up comic and I don't really care what people think.At the Furious Flower Poetry Conference in 1994 (pictured right), she was one of the first writers to receive the Lifetime Achievement Award, and three years later I convinced her to join the Wintergreen Women Writers Collective, a group that has been meeting annually since 1987. As a Wintergreen Woman, Evans contributed "My Father's Passage" to the 2009 collection of essays, Shaping Memories: Reflections of African American Women Writers. During the editorial process for that book I read some of her unpublished writing that helped me to understand the importance of music to her; written in about 2005, it gives a rare glimpse into Evans' very private life, so I'm including an excerpt here. When I was twelve, I realized that music was language. That it spoke my most private thoughts.

That when I was furious at my beloved single-parenting father, I could attack him, could express that fury with music that spoke my all-encompassing anger with the kind of violence I could otherwise never display. But music also quieted me, brought serenity when I wore myself out with crashing chords. I could then speak sunrise and soft winds. Music said what I had no language for and provided me with emotional transitions. I know now that with insightful mentoring and guidance, I had the genes, the "right Stuff" for composing. For that was (is) all I ever wanted to do: Sit at the piano and speak. Seething, without language, too frozen to respond, What-in-hell?A year, or maybe only moments later, he re-crossed the room, the lead-sheet outstretched. "You will never be a songwriter, " he pronounced. You can't write lyrics.

Rage had blurred my eyes; I doubt I saw him rejoin his friend. Outrageous, arrogant, insulting, white assumptions of superiority again, how-dare-he! All of the above-the world had still not provided me with the requisite profanity-but that was my defining moment. The moment when, involuntarily, words began to move abreast of music, and I eventually began to drift into a world of poetry I had never aspired to enter, for lyrics have always only been the engine that ran alongside my music. Then, and now, it is music that consumes me; music is my Kilimanjaro.

Evans' persistent pursuit of music is a dominant factor in understanding and appreciating her literary contribution. Her rage at having someone tell her what she couldn't do predicted her parallel development as a song writer/composer and poet, and in each art form the political significance of her artistic expression was not lost. In a conversation with Val Gray Ward at James Madison University in 1994, Evans describes the political situation in this country as a grotesque pas de deux in which dancers pull and strain against one another in movements of freedom and oppression, power and powerlessness, resistance and compliance. She writes in her 2006 book of essays, Clarity as Concept: a Poet's Perspective, about our need "for a literature that influences attitudes and concomitantly behavior, a literature that demystifies the systems, allowing us to understand ourselves within them; a literature that delineates the comprehensive nature of our oppression, and the subtlety of our colonization; a flexible literature responsive to all the people, moving when necessary to incorporate itself with music, dance, and art in ways that are not merely creative but committed to the destruction of our psychological bondage" (94).A member of the Black Arts Movement, Evans was a change agent who did not confuse movement with progress, a poet who danced to her own song. Though I will miss her razor sharpness, her brilliance, her insistence on speaking truth to power, I will miss more her indisputable love for Black people. For her 2007 collection titled Continuum, in the poem Who Can Be Born Black? She writes: Who can be born black and not sing the wonder of it the joy the challenge. One of the major tropes in her poetry, song, carries cultural authenticity: the history, the lineage, the pride, the character of our people.

Thank you, Mari, for your song.